What types of data sets should be mapped, which shouldn't

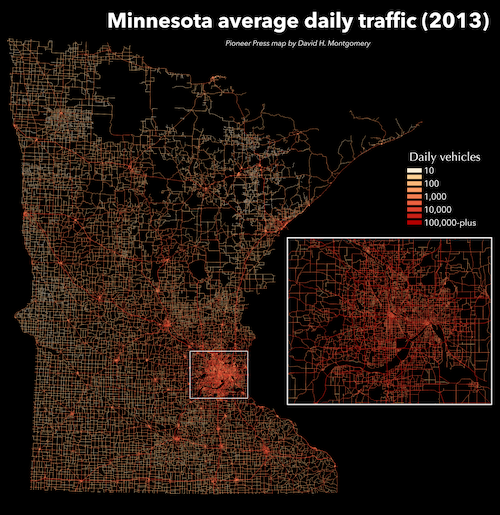

Is there a geographical story?

Would a table or chart tell the story just as well?

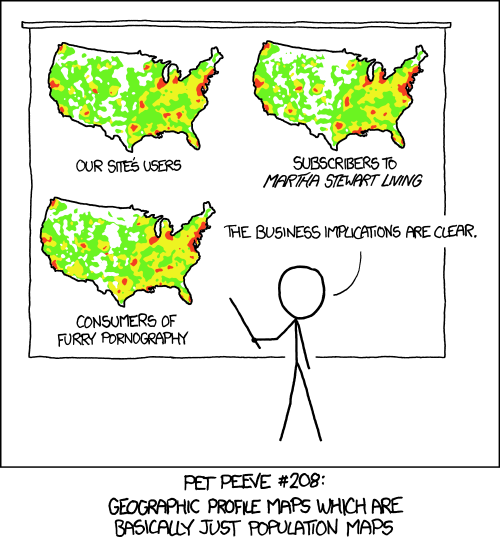

Am I just mapping where people live?

What you can do with QGIS

Analyze geographic data

Create static maps for display

Generate files for interactive map (CARTO or leaflet.js)

Where to find geographic data: national, state, local

Alexandra Kanik tries to keep this mapping resources doc up to date. It could use some reworking and some additional resources, though, so feel free to contribute!

National data

Census shapefiles DATA.GOV National Historical Geographic Information System

State data

State government websites (such as the Minnesota Geospatial Commons)

College and university research centers (Penn State has this one for Pennsylvania)

IRE Census data

National States Geographic Information Council

Local data

Census places - Census places are defined as incorporated places, usually cities, towns, villages, or boroughs. You can read up more on that here.

Your local government should have shapefiles and other data that relate to your local region. Give them a call or visit their website. Here's the GIS office for the City of Pittsburgh.

Geocoding tools

Peter Aldhous's Refine geocoder - this is nice because it uses geocoders that are, in most circumstances, legal to use. It also geocodes your data using two geocoders so you can compare the results. And it's free! Rate limits may apply.

Census geocoder - Free but I've found it to be a little less accurate. Rate limit: 1,000 addresses at a time.

Here's a more complete list of geocoding tools and APIs

Common data types

Shapefiles

- .shp - the feature geometry

- .shx - positioning index of the feature geometry

- .dbf - the data attributes for the features. This can be opened with editors like excel.

- .prj - projection file. This can also be opened and analyzed. Especially if you're having projection issues.

GeoJSON

Delimited text layer

CSV

id, city, state, population 001, Pittsburgh, PA, 310885 002, Columbus, OH, 822092TSV

id city state population 001 Pittsburgh PA 310885 002 Columbus OH 822092PSV

id|city|state|population 001|Pittsburgh|PA|310885 002|Columbus|OH|822092

Types of GIS data

Raster

Vector

Point

Line

Polygon

What is a .qgs file?

When you save a QGIS map file, it will save as a .qgs. This file is a configuration file. It basically just references the files that you load into QGIS. IT DOES NOT HOLD ANY OF YOUR DATA. This means if you move the shapefiles you load into your map after you save it, your map will break.

So establish a working directory for each map you work on. Put your shapefiles and your map file in there and don't move them around.

This might seem like a weird, crappy way to organize things. But it's not. And here's why.

QGIS isn't perfect, and neither are you. Sometimes you come up against errors in behavior that you can explain. So your only recourse is to shut 'er down and reopen the program.

And sometimes, that doesn't work either. So you need to scrap your map file.

Now, if all of your work depended on that one .qgs file, that would suck hardcore. But since your shapefiles and data are separate files, and since you've taken crazy good process notes, you're totally fine.

Naming your files and taking mad notes

There are going to be projects you work on that will require you to slice and dice a shapefile in many different ways. You need to be careful what you name each file so you aren't analyzing old shapefiles.

I would strongly recommend taking detailed notes about how you change shapefiles so you can return to the notes in case you lose track of which file is which, or if something goes wrong and you need to diagnose a problem.

What is a projection?

So the earth is round, right? Turns out it's not the easiest thing to make something round and three-dimensional look flat. But to hell if we don't try.

That's basically what projections are, flat representations of our round world. Lots of people have taken a stab at making the best projection, but not all projections are created equal.

Depending on the scope and span of your data, you may want to stick to a more local, granular projection. But if you're trying to show the whole world things are going to get a little wonky at some point.

Mapping projections from the 1936 Oxford Advanced Atlas compiled by John Bartholomew, cartographer to His Majesty the King

* I've collapsed this section because while it's very important to understand projections, they are also amazingly confusing and might serve only to confuse the novice map maker. Just know to return to this topic once you feel more comfortable with QGIS and displaying and analyzing geographic data in general.

Demo

In this demo, we're going to be creating a map that overlays Pennsylvania nursing homes with abandoned mine data.

This is a blank map.

The working directory

- Download the data

- Choose your working directory, and stick with it

A working directory is a place on your computer where you house all of your map shapefiles. Once a shapefile is added to the working directory, it should not be moved around because that can break the file path and therefore your map.

In the example above, abandoned-pa-mines-data is the working directory.

This is what you'll see if you move layers and map files around

Adding data

We're going to be focusing on VECTOR LAYERS and DELIMITED TEXT LAYERS. These are the layers you will use most often.

Adding vectors

- Click the

vector layer button

vector layer button - Navigate to your working directory

- Add

tl_2014_42_county-->tl_2014_42_county.shp - Let's talk about projections now.

- Let's pause here and play around a little with styling!

Styling

- Right-click or double-click the layer

- Select the Style tab

- Style accordingly

Adding more layers

- Add

aml_inve-->aml_inve.shp - Add

pa-nursing-homes-20150220-->pa-nursing-homes-20150220-shp-->pa-nursing-homes-20150220.shp

Adding delimited text layers

There are two types of delimited text layers you can add: geographic and non-geographic.

Geographic delimited text layers

So we've already add the pa-nursing-homes-20150220 as a shapefile, but there's another pa-nursing-homes-20150220 data file in our working directory.

- Click the

delimited text layer button

delimited text layer button - Navigate to your working directory

- Add

pa-nursing-homes-20150220-->pa-nursing-homes-20150220-geo.csv

On the data import screen, we have many options. Most of them are self explanatory. But look under Geometry definition. This is where we will be telling QGIS that we have a delimited text layer that has geographic data.

Make sure Point coordinates is checked.

Then set your latitude and longitude fields

Write this down:

Latitude = Y

Longitude = X

Non-geographic delimited text layers

If your delimited text file doesn't have those latitude and longitude columns, you can still import the data, but nothing will be mapped

This is often useful and necessary when you're trying to join non-geographic data to geographic data. Michael Corey goes over that in his presentation.

- Click the

delimited text layer button

delimited text layer button - Navigate to your working directory

- Add the

pa-nursing-homes-20150220folder -->pa-nursing-homes-20150220-source.csv

Because we have no geometry in this file, QGIS won't let us add it to the map until we tell it that there's No geometry (attribute table only)

The difference between On-the-fly (project-level) projection and layer projection

On-the-fly projecting

On-the-fly projecting is a way of setting the project-level projection so that subsequent shapefiles added to the project assume that specified projection.

You'll want to set this on-the-fly projecting before adding any data to your map.

NOTE: On-the-fly projecting does NOT actually change your shapefile's projection. So next time you use this shapefile in a new map, it will revert back to whatever projection it had before you added it to your on-the-fly map. If you want to actually change a shapefile's projection see this section.

Changing a layer's projection

If you'd like to change a layer's projection instead of just changing how the layer looks in the QGIS system, you'll need to follow these steps.

- Right-click the layer you'd like to change

- Select "Save as"

- Click the "Change" button near the CRS section

- Choose your desired coordinate system and click "OK"

- NOTE: this process is going to create a NEW shapefile from your existing shapefile, so make sure to name it something you'll remember

- Name your new shapefile and add it to your working directory with the "Browse" button

You might be thinking... well that didn't seem to change anything. But close down QGIS, open a new map, and add that newly projected shapefile. You'll see that it now looks much different. Much more like Pennsylvania is expected to look.

Selecting by location

Now we want to take a look at only those nursing homes that sit on top of abandoned mines.

- Navigate to the Vector menu > Research tools > Select by location

- Select features in = the shapefile you want to refine

- That intersect features in = the shapefile that will determine which features are selected, the intersect layer

- Right-click layer and select "Save as"

- Follow normal saving procedures, but make sure to check the "Save only selected features" box

- You probably want to add this file to the map after it's created, so check "Add saved file to map" also

Analyzing the attribute table

- Right-click the layer and choose "Open Attribute Table"

- Navigate to where the layer is stored in your working directory and open the .dbf file with an editor like excel or libreoffice

Exporting

So you've got a nice map here. What can you do with it?

There are ways to get from QGIS to an interactive map, but we're going to focus on something quicker: how to export a static image of your map.

There's two ways: one easy, and one more complex but powerful:

- The easy way: click Project > Save As Image.

- The powerful way: click Project > New Print Composer

- Name your map

- Click the

add new map button. Draw a rectangle to fill the canvas.

add new map button. Draw a rectangle to fill the canvas. - Click the

add label button. Draw a rectangle where you want a title.

add label button. Draw a rectangle where you want a title. - In the sidebar, type what you want the label(s) to say, and style.

- Click Composer > Export as Image. Pick a name and size.

- Admire your handiwork.

You mean you want more mapping?

Go to qgis.org to download the mapping program yourself.

This is only the very beginning of what's possible with QGIS. Here's a link to Michael Corey's presentation where he covers joining datasets within QGIS, simplifying shapefiles and grouping points by location.