Standing athwart history yelling "hard to port!"

The 16th Century wasn’t a good one for the Scots. It had started so well – the Scots had finally triumphed once and for all over the hated Englishmen, parading through the streets of London as conquering heroes. And then Martin Luther nailed his theses to the church door, and everything went to heck.

That is not, of course, the real course of events in Renaissance Britain, though if there ever were a time for Scotland to strike, the Wars of the Roses might have been the moment. (And they did, in fact, meddle in the Wars of the Roses, but to no avail.) But it’s Scottish history I decided to alter the past few days in the “grand strategy” game Europa Universalis (III, to be precise).

I’ve long been a fan of the Civilization series of games, where you take control of a civilization and, through war, economics, science and diplomacy lead them to glory. Europa Universalis is a similar concept, with a few key differences: unlike Civ games, where you usually play out on a randomly generated map, EUIII always takes place on the same world – ours, between 1399 and 1820. Whatever date you pick, the world is a close mirror of the actual situation at that time. But from then on you’re in control.

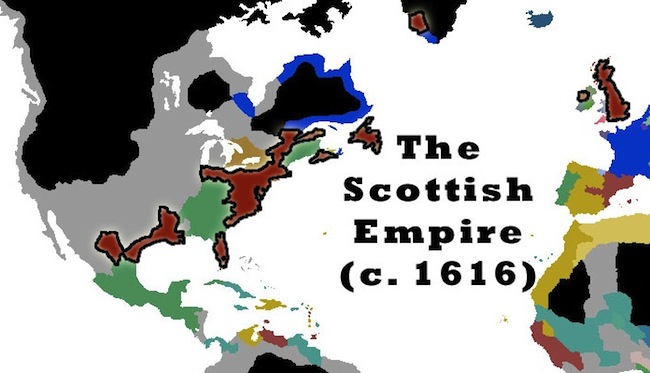

In my case, it was Scotland – and not England or France or Spain – who colonized the New World. The Scottish mariners had a premonition about sailing west from the bases they seized on Iceland, and soon enough were building a string of colonies from Newfoundland south along the Atlantic coast of America.

You’ve got plenty of other options. You can replay the Thirty Years War and win a smashing victory instead of the grinding stalemate of real life. You can take over a small Italian city state and form an Italian nation 300 years ahead of schedule. You could take over Granada and resist the reconquista, taking back Spain and who knows what else for Islam. Play as Byzantium and throw back the Ottomans at the gates of Constantinople, revitalizing the Eastern Empire.

You’re not totally free, though. No matter who wins the battles, the EUIII game engine keeps the broader historical trends rolling. Catholicism splinters in the 16th Century, with Lutherans and Calvinists popping up all over the map. This is what nearly brought my two-continent Scottish empire to grief.

See, my Scottish kings in that century didn’t care much about religion. They had a tolerant, ecumenical attitude you could call centuries ahead of its time. They waved off reports about Protestantism taking hold in one province or another and concentrated their efforts on overseeing the great colonial venture. That part, at least, went well, with brave Scottish settlers putting down roots across the continent centuries ahead of what those weak Englishmen managed to do:

But high ideals of toleration, it turns out, don’t necessarily work when everyone’s convinced their neighbor is doing the devil’s work by worshipping in the wrong church. So the Scottish Wars of Religion dragged on for a century, a constant stream of uprisings never quite rising to the level of civil war. The Scottish monarchy put them all down, the elite Stuart Horse galloping from the Highlands to Wessex and back on a regular basis to fight various Lutherans and Calvinists, as well as impoverished peasants and opportunistic would-be usurpers.

Eventually, there was only one thing to do: convert the majority of the Scottish citizens to one faith. I weighed Lutheranism and Calvinism carefully before deciding to stick with Catholicism, so I embraced the Counter-Reformation and sent the Jesuits out to minister to the populace. (It was a choice of convenience: Scotland’s British territories were pretty evenly split between Catholicism and Protestantism, but the American colonies were uniformly Catholic. Converting the English back to Catholicism required less walking than turning the Americans into Protestants.)

This little narrative is perhaps the greatest charm of Europa Universalis. By putting you in the driver’s seat of something recognizable – world history – it lends itself elegantly to narratives. It’s the charm of alternate history, the “what if?” game. What if the Scots had colonized North America before the English? What if the dukes of Burgundy, and not the kings of France, came to dominate western Europe? What if the Bohemians had conquered the fractious German princes and archbishops, establishing a central European empire headquartered in Prague? You can play out all those scenarios – if you’re good. (Playing as Scotland, I found that my initial plan of ignoring England and going all out for America wouldn’t work – the English, sooner or later, will invade, and then you’re doomed. So I used the old Scottish trick of allying with France, only successfully – welshing (ha) on my alliance when the French went to war, I just waited six months and THEN invaded England when their army was dug in around Calais.

The game itself is much more complex than the more popular Civilization series (or, at least, it tries less to hide its complexity from the user). There are tools to play the game as a great conquering empire, as a maritime colonial power, as a tiny merchant republic, or what you will. Page after page of charts and tables will give you all the detail you could handle about your empire and your rivals. It’s a little overwhelming, but also a little addicting, as several dangerously late bedtimes for me this past week bore witness.

The ways in which the game constrains you are also interesting – and a little troubling. If you colonize Africa, you participate in the slave trade – you don’t have a choice, it happens. I’m pretty sure this is a deliberate decision by the game designers – slavery is so morally abhorrent for modern players that almost everyone, I hope, would reject it, thus building in a big ahistorical fork in the road in a game that’s supposed to unfold as an alternate version of real history.

You DO have a choice when it comes to how brutally you colonize. Provinces in America and Africa that aren’t occupied by empires and confederacies can be colonized – but many of them have natives there. The more of them, and the angrier they are at you, the more difficult and expensive it is to plant a colony. So the game gives you an option, if you’ve got a military unit in the province: “attack natives.” If you can win the fight that provokes, you commit some localized genocide and open up some prime real estate – if you’re willing to bear the stain on your soul of having deliberately murdered simulated human beings.

I didn’t do this in my colonization, instead suffering through a number of failed attempts to plant colonies. I also didn’t do what computer controlled Portugal did to get a quick-and-easy North American empire – they just sent in their conquistadores and took over the Creek empire, Aztec- or Inca-style. In the north, I chose to leave the Hurons in place, instead showering them with gifts and signing an alliance.

Of course, if you don’t kill the natives and colonize anyway, it’s probably not going to go well for them in the long run, though the population takeover of European colonists happens in the background if you don’t deliberately attack the peaceful villages. What EUIII teaches you is it’s basically impossible to replay that period of history and NOT be a monster to one degree or another. If you don’t colonize the New World, you focus your efforts on the Old, and Europe wasn’t a very peaceful place during this time, either. It’s possible, I suppose, to pick some small merchant republic somewhere and buy off your neighbors for hundreds of years with your trading profits, never going to war. But in most cases war will come to you, whether you fabricate a casus belli to grab your neighbor’s land, he does the same to you, or the alliance you signed to protect you from your neighbor ends up dragging you into someone else’s war.

All this action, of course, happens without the slightest bit of blood. You’re not gunning down your enemies Doom-style; you just click on a military unit and order it into a province, and sooner or later it tells you if you won or lost and how many casualties each side had. It’s bloodless slaughter, world conquest reduced to numbers and colors on a map. Is one more morally sound than the other? My instinctive reaction is to prefer the detached strategist ordering around thousands of subjects to the adrenalin-rushing soldier actually doing the killing – but then, whenever I’m faced with a dilemma, my solution is always to detach myself an analyze the situation. And, typically, I can see the other point of view: the murderer may be abhorrent, but he will send far fewer people to their graves than the general who never sees a spot of blood from his distant command center. (Jonathan McCalmont argues this very point here.)

It also feels worse to order my soldiers to attack the natives around Massachusetts Bay than it does to, say, click the “raze city” button in Civilization when you’ve conquered a rival. It’s the closeness to history that makes the narratives you construct so appealing – they also make you feel the consequences of your actions more than a more abstracted game.

Still, I don’t think this kind of moral dilemma over a computer game is close to serious enough to stop me from diving back in to Europa Univeralis. I think next time, I’m going to ignore America and try to conquer Europe. Perhaps as Denmark? It may be bloody, but at least it’ll be challenging.