Movie review: "The Secret of Kells"

In 2009, Irish director Tomm Moore released an idiosyncratic animated film, “The Secret of Kells.” It was widely praised by critics, but apparently made less than a million dollars at the box office.

Having watched the film tonight, I understand both why that is and why that’s such a shame.

To start with, “Kells” looks like no other cartoon out there. Its art is highly stylized, evoking the flat perspective of medieval illumination — such as illustrated the real “Book of Kells” on which the movie’s story centers. Frequently, the images coalesce into simple geometry with an emphasis on curves: circles, arches and swirls repeat endlessly, whether in the human abbey:

Abbott Cellach (left) and his nephew Brendan stand in the planning room for the Abbey of Kells in the 2009 movie “The Secret of Kells.”

or in the wild forest beyond:

Brendan (left) stands atop a tree with the forest spirit Aisling in the 2009 movie “The Secret of Kells.”

Witness, too, the striking use of perspective. Lack of realistic perspective was one of the highlights of pre-Renaissance art, something the “Kells” animation deliberately recreates. It’s a little jarring, at first, but eventually it becomes quite charming.

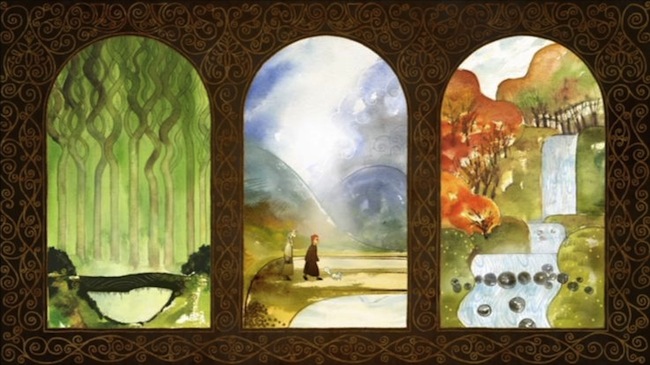

Medieval art is also deliberately echoed in a number of scenes that evoke triptychs:

Art from the 2009 movie “The Secret of Kells” evokes a medieval triptych, with action unfolding in succession across the three panels.

or cathedrals:

The entrance to the forest in the 2009 movie “The Secret of Kells” resembles the nave of a great Gothic cathedral.

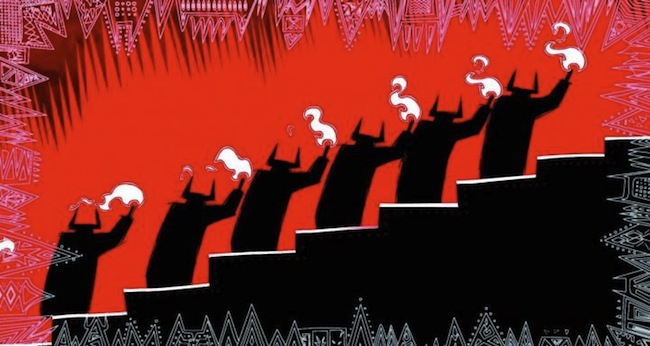

At other times the art changes. The marauding Northmen of movie are depicted as angular shadows, darkness broken only by their blazing eyes and the gleaming swords and raging fire they bring with them as they raid across Ireland:

Vikings in the 2009 movie “The Secret of Kells.”

Perhaps my favorite sequence is when protagonist Brendan descends into darkness to battle a pagan god for possession of a powerful artifact. The deity, Crom Cruach, is represented as an angular serpent who chases Brendan through a maze made of his own coils — a maze that seems two dimensional until suddenly the perspective turns and we follow Brendan down another axis:

The Celtic deity Crom Cruach guards an artifact the boy Brendan seeks in the 2009 film “The Secret of Kells.”

The art is so different from anything else that in pondering the movie it’s easy to get swept up in it. But believe it or not, “Kells” is interesting on the story side, as well.

Its plot concerns a boy, Brendan, who lives at the Abbey of Kells in a remote part of Ireland. The abbey’s primary purpose is a refuge, both for people and for the knowledge the monks are trying so desperately to preserve in the form of books, meticulously hand-written and illuminated. This is historically accurate — Irish monasteries played a major role in preserving the written word during the Dark Ages.

The menace to both the people and the knowledge comes from the Northmen, Vikings who are burning and marauding across Ireland in search of wealth. This, too, is relatively accurate, though of course the movie’s caricature of Vikings as shadowy killers is something less than the full picture.

Brendan’s uncle is the Abbot of Kells, Cellach, whose determination to protect his people from the Northmen has become a monomania. Cellach has put aside the books he used to create and focuses all his energies — and those of everyone around him — on constructing a massive wall around the abbey to keep the Northmen out. Anything that takes away from that effort — like Brendan’s fascination with illustrating the Book of Kells — draws Cellach’s ire.

“The Secret of Kells” paints Cellach as misguided, trying to wall the world away instead of embracing it. The only solution to the menace of the Northmen, the wiser Brother Aidan says, is to run. But it’s not clear that’s the case. Yes, in his determination to finish his wall, Cellach has lost sight of some of what he’s trying to protect. But the danger of the Northmen is real, and Cellach’s defenses fail not so much because they’re foolhardy but because the Vikings come too soon, before all is finished. Some of what Cellach has built actually works, saving some of the villagers from the marauders.

The implication in the above paragraph is worth considering fully: this is not a movie for small children. While most of it is fanciful, involving faeries, pratfalls in the abbey and the forest, and a young boy torn between a stern father figure and a nurturing father figure, the movie’s climax is a scene of shocking darkness — all the more shocking because of the innocence that came before it. The Vikings storm the Abbey of Kells in a frenzy of fire, swords and arrows. Cellach is shot and cut down as he tries to run to protect Brendan. Villagers trying to reach safety in the abbey’s tower fall to their deaths when the stair collapses. An equally grisly fate awaits the monks who take refuge in the church, whose prayers and chants are interrupted when the Vikings kick down the church door.

All this is shown in a highly stylized fashion, and other than Cellach, you never actually see the deaths of any of the monks or villagers. The movie cuts away, for example, after the Vikings barge into the church — but what happened is clear. I’m not an easily shaken person, and I was a little disturbed watching the scene. I imagine your typical eight-year-old would be terrified. That’s not to say they couldn’t handle it, but I would be very careful about showing “The Secret of Kells” to a child until I was sure they were ready.

As an adult, I appreciated the uncompromising vision of Moore in portraying the sack of Kells. More than anything, it humanized Cellach, who had previously been something of an antagonist, intent on stopping Brendan from having fun, creating art or exploring the world. Suddenly the viewer is forced to accept that Cellach had a point about the dangers beyond. It’s not that either Cellach or Brendan was wrong. Both had points, about the need for protection and the need to not lose sight of what must be protected.

Finally, it’s worth exploring one more curiosity of “The Secret of Kells” — the almost complete absence of Christianity from a movie set in an abbey, about monks creating a book that’s not just a work of art but is (though the movie never indicates this) a Bible. While the monks make reference to praying, and the setting includes crosses and a church, neither “God” nor “Jesus” are mentioned, nor the Biblical nature of the Book of Kells. I understand somewhat of the reasoning behind this — you don’t want to turn a general audience movie into something overtly religious. But I think there was a middle ground between ignoring the monks’ Christianity and embracing it.

This is particularly true because the movie does not shy away from the pagan side of things, with both the faery Aisling and the god Crom Cruach presented as existent beings of real power. Moore doesn’t DENY the abbey’s Christian nature, as evidenced by his inclusion of crosses and the church, but it’s definitely a conscious decision to shy away from overt Christianity. It would have been so easy to do, too — a couple passing references to God in the dialogue, perhaps a scene of a character at prayer. But the selective ahistorical portrayal rubs me the wrong way. Yes, our modern day society is much less religious than Dark Ages Irish monks, and yes this is a work of fiction that needs to reflect the worldview of its audience as well as its inspiration. It would have been a braver artistic choice, though, to show the same respect to the monks’ faith as he did to the pagans’.

It’s interesting that I only watched “The Secret of Kells” Monday night because the movie I originally intended to watch was unavailable on Amazon Video On Demand. I had intended to finally see “A Bug’s Life,” the only part of the Pixar canon I’ve never seen. When that wasn’t available, “Kells” stood out to me as a movie I had heard good things about. But in its release year, “Kells” lost out on the Best Animated Picture award to Pixar’s “Up.” Now, I have no grudge against “Up” — I enjoyed it greatly, both concept and execution, and thought it one of the best movies of the year. (Certainly better than the uneven “WALL-E,” which had a superlative, one-of-a-kind first act, a great second act, and a paint-by-numbers action-riddled third act that dragged the whole movie down from its initial artistic heights.)

But as great as Pixar movies are (even the weakest, “Cars”), as striking their premises and as flawless their presentations, there’s something fundamentally conventional about them. “Toy Story” was unique, certainly, and “Monsters Inc.” perhaps the most original of the lot, but later films tend to repeat the same basic plot structures. “WALL-E,” with its dialogue-free first act, came the closest of Pixar’s latest films to breaking out of this mold, before ultimately falling back to earth with a thud. We as audiences ooh and ahh over Pixar’s boldness in making movies with unconventional heroes like a cooking rat or an old man, but Pixar asks us only to accept the originality of their concept, not to challenge us with unconventional methods of storytelling. (When Pixar does challenge those conventions, like the first act of “WALL-E” or the tear-jerking introductory montage in “Up,” those moments are rightly recognized as exceptional.) Pixar films are superb examples of what they are, but in the end what they are is rooted in mass sensibilities that can be accepted by everyone without much effort.

“The Secret of Kells” is a different cat. And that’s both why it made less than a million dollars at the U.S. box office, and why more discerning filmgoers owe it to themselves to give it a watch.