The paradox of red state Democratic success

(This post has been adapted from work previously done for the Argus Leader and its Political Smokeout blog by David Montgomery.)

Many Democrats in Republican-dominated states like South Dakota derive what little political pleasure they have from the party’s national victories. While electing a Democratic governor in South Dakota can seem nigh-impossible at times, Democrats like Barack Obama and Bill Clinton regularly take control of the national reins of power thanks to more liberal voters in other states.

But in South Dakota, at least, history suggests Democratic national victories are actually devastating for the party’s hopes of winning local elections.

Dating back more than 60 years, Democrats have controlled around 10 extra seats in the South Dakota Legislature, on average, in the years when a Republican occupies the White House, compared to when a Democrat is running things in Washington, D.C.

In those years when a Republican is president, moreover, Democrats have tended to gain an average of around three or four seats per election.

But when a Democrat such as Lyndon Johnson, Jimmy Carter or Clinton has been president, South Dakota’s Democrats lose an average of four seats in each election.

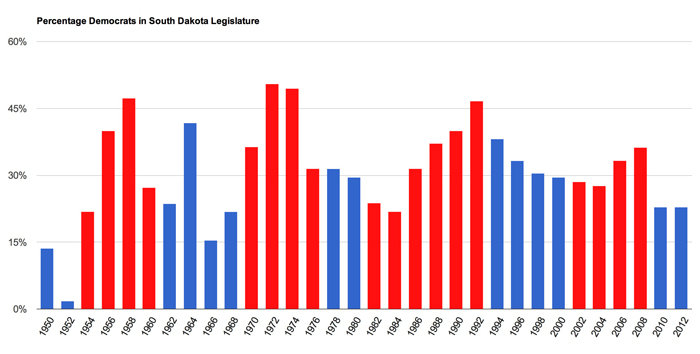

This trend is striking when viewed graphically. The following chart shows the percentage of seats in the South Dakota Legislature occupied by Democrats, and is colored by the party affiliation of the president in the year of each election. (So 1976 is red even though Jimmy Carter won that year because Gerald Ford was president at the time of the vote.)

The slope is unmistakable — with a few outliers (notably the 1964 Lyndon Johnson landslide), Democrats steadily gain seats in the GOP-run years, and fall backwards otherwise.

These trends don’t prove that Democratic presidents are causing Republican victories in South Dakota, merely that the two tend to happen at the same time.

But Jon Schaff, a political science professor at Northern State University in Aberdeen, said he can see how Democratic presidents might make it tough for local Democrats in conservative states such as South Dakota.

“I could see that when a Democrat is in office, doing things that maybe a majority of the state doesn’t like, the … unpopularity of the national Democratic Party gets attached to local politicians,” Schaff said.

Another explanation for the trend could be the effect of Democratic presidents on Republican voters.

“At times when the national Democratic Party is in ascendancy, Republicans in the state become more partisan,” he said.

The only times Democrats have taken control of one or both houses of the Legislature — the Senate in 1958, 1972, 1974 and 1992, with a deadlocked House in ‘72 — have all been elections with a GOP president. Similarly, the only five times in this period that a Democrat has been elected governor were during Republican presidencies.

That’s not to say there’s not plenty of other possible explanations. Democratic gains in the 1970s under presidents Richard Nixon and Gerald Ford could involve the national anti-GOP backlash after the Watergate scandal. Their gains in the 1980s under President Ronald Reagan might be connected to Reagan’s unpopular farm policy rather than anything more fundamental about Reagan’s political affiliation.

One political watcher, former South Dakota Republican Party chairman Joel Rosenthal, said effect could simply be a coincidence. The real factor, he suggested, was that some Republican governors have been more vigorous at energizing and organizing the state GOP than others.

“It could have a lot more to do with Bill Janklow being on the ticket or being governor, or Dennis Daugaard,” Rosenthal said, pointing to two governors who have served at times when Republicans did well in the Legislature.

Only three governors were in office for both Democratic and Republican presidential administrations: Janklow (under Carter, Reagan, Clinton and Bush II), Mike Rounds (under Bush II and Obama), and Sigurd Anderson (under Harry Truman and Dwight Eisenhower). The sample size there is too small to draw any strong conclusions, but Janklow under Democrats saw Democrats lose an average of just under three seats per election, while Janklow under Republicans saw Democrats gain an average of a quarter seat. Rounds’ one election with a Democratic president was a Republican landslide when Democrats lost more than 13 percent of their seats, while his elections under Bush saw Democrats pick up an average of several seats each year. Anderson’s election under Truman saw the Democrats nearly wiped out in the state, while once Eisenhower took office they rebounded vigorously.

Shortly before the 2012 election, the then-chairman of the South Dakota Democratic Party dismissed the correlation.

“I think there’s probably a number of factors outside who’s in the White House at play in those elections,” said Ben Nesselhuf, chairman of the South Dakota Democratic Party until July 2013. “By and large, South Dakotans have a pretty good understanding of what their Legislature’s about and who they’re sending there, and the difference between the national parties and the state parties.”

But after the voters in November 2012 returned the same number of Democratic lawmakers despite a vigorous SDDP campaign, Nesselhuf privately pointed to this analysis as a reason why Democrats didn’t regain some of the seats they had lost in the 2010 Republican landslide. Some commentators, including this writer, had expected Democrats to gain back some seats under the evocatively named theory of the “dead cat bounce” — a party that suffers a landslide defeat will lose seats they normally win, and thus will be well-positioned to retake them once the landslide is over. That didn’t happen, and Nesselhuf suggested it was because South Dakota Democrats were struggling against the massive unpopularity in South Dakota of a Democratic president.

Rep. Bernie Hunhoff, the Democratic leader in the state House of Representatives, said Democrats tend to get “none of the benefits” of having a Democratic president, since the national party rarely invests significant resources in South Dakota.

“Both parties write off the state,” Hunhoff said. “And yet we get whatever negatives there might be, because everyone likes to blame the party in charge. That was certainly true under Clinton and Obama.”

View the data used in this analysis here.