An unscientific experiment in new media forms

Alexis Madrigal at the Atlantic terms new media ventures like FireThirtyEight, Vox, the Upshot and others “method journalism,” in that they’re primarily focused on how they report the news, rather than what news they report:

In a world where traditional beats may not make sense, where almost all marginal traffic growth comes from Facebook, where subscription revenue is a rumor, where business concerns demand breadth because they want scale… a big part of the industry's response this year has been to create sites that become known by how they cover something rather than what.

FiveThirtyEight’s method is using data and statistic to cover the news. Vox is about explaining the news. Circa is about prioritizing news for viewing on mobile phones. The Upshot is about “plain-spoken, analytical journalism.”

As a reporter myself interested in exploring new ways to gather and produce journalism, I’ve been following these new ventures avidly. And yesterday, completely unintentionally, I conducted an unscientific experiment on my work blog into how readers respond to these various new approaches to journalism.

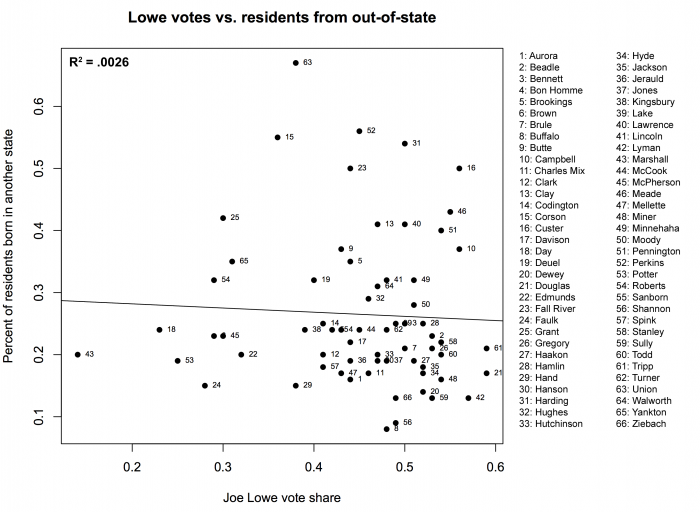

In the morning, I posted a FiveThirtyEight-style data analysis (in this case, I was literally inspired by an article FiveThirtyEight founder Nate Silver had written). After hearing an argument about why a gubernatorial candidate born and raised elsewhere had lost his election, I cross-referenced Census data and election results to figure out whether dislike of “carpetbaggers” had swung serious votes:

If dislike of people without deep roots in the state contributed to Lowe's defeat, then you'd expect him to do worse in counties where there were fewer transplants — who presumably don't have the same value on deep local roots, since they lack them themselves...

... In this case, the correlation between Lowe's support and the rate of out-of-state residents is essentially zero. You can see it for yourself: there's no pattern there. Lowe did well in some counties with lots of transplants, and in some counties with few transplants. Among counties with similar levels of out-of-staters, Lowe's vote share varied by as much as 50 points.

A few hours later, I posted a Vox-style article, explaining something that bewildered more than one person I know: why the closure of a brief section of Interstate 29 caused authorities to announce a 455-mile detour.

Why would authorities tell motorists to go through Des Moines when they could drive on back roads through Iowa or Nebraska to avoid the flooding, at a much lower cost in added time and miles? After I snarked a little bit on Twitter, a spokesperson with the state Emergency Operations Center called me up to explain. "Federal law requires that the interstate system in all of America must be connected," said Jonathan Harms, a spokesman with the Emergency Operations Center. "The DOT and the Federal Highway Administration needs to have some sort of route that collects all the interstates in America." Officials are, therefore, obligated by law to present an official detour that stays on the Interstate system. But they also can offer other, more direct detours. Like [this one](http://www.gannett-cdn.com/-mm-/e2a210702f45d5e9ef4c354f11065f5e0296bb30/c=33-0-2950-2191&r=x383&c=540x380/local/-/media/SiouxFalls/davidmontgomery/2014/06/19/1403201876000-I-29DetourMap.png)... that's only an extra 20 miles and half an hour.

I had fun with both posts. But they got very different responses from the public.

The FiveThirtyEight-style post provoked a few intelligent responses by other close observers of South Dakota politics, but generally didn’t attract a wide audience. In its first day, it was shared on Facebook seven times — at least two of which were by me. Six weeks after its post, on July 28, it had racked up a grand total of 148 views.

The Vox-style post didn’t really spark any discussion. (There had been some Twitter discussion about the detour before my post on why the long detour was proposed, but nothing once I explained the reason for the seemingly absurd detour.)

But lots of people read and liked it. In its first day, it was shared on Facebook a full 344 times. And six weeks into the future it’s got a full 4,759 total views and is my third most-viewed story of the past three months behind two articles that got national attention.

As I mentioned above, two posts is in no way a scientific study of how people respond to data-heavy analysis vs. explanatory journalism. FiveThirtyEight has plenty of posts go viral, while Vox has written some wonky analysis to go along with its usual explainers aimed at making the news understandable for ordinary people. But it’s not surprising to me that my unscientific experience yesterday showed a lot more people are interested in having things explained to them in a straightforward manner than deep dives into the numbers.

(This post has been updated with new data.)