The accidental republic

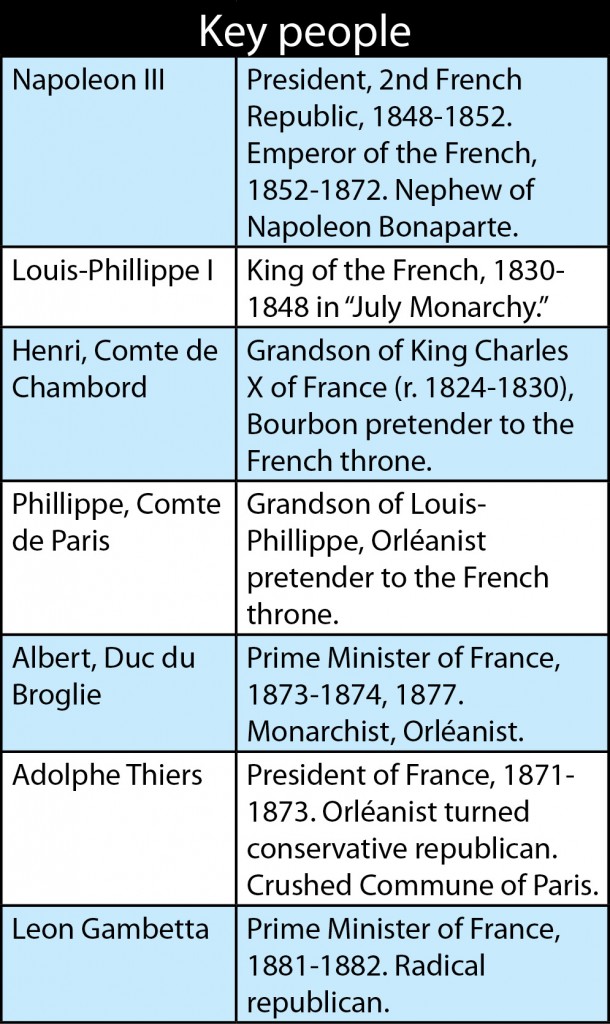

In 1870, Napoléon III abdicated as Emperor of the Second French Empire. Parliamentary deputies from around the country met, first in Bordeaux and then in Versailles, to determine the next form of French government, and there was little reason to expect a republic.

History alone suggested authoritarian rule was most likely. Most of French history had been under kings. Even the tumultuous 78 years since King Louis XVI was deposed saw France governed by Bonaparte emperors for 29 years, by kings for 36 years and by republics for 15 years — most of those years in the last century, under the bloody Terror: republican dictatorships with an emphasis on “dictatorship.” The last French republic had been a brief chimera, an interregnum between monarchy and empire.

Recent history too saw the democrats crushed and discredited. Parisian workers and radicals had risen up in the Commune of Paris and were brutally crushed in the semaine sanglante or bloody week, in which 17,000 or more Communards were killed (10 times the number who fell to the guillotine in 1793)1 — and the radical leaders imprisoned or exiled.

The nascent republic’s “very legitimacy… was fading by the day, with hard-line monarchist representatives sniffing for any signs of weakness that might allow them to usurp power.”2

It’s no surprise that when new deputies were elected in 1871, about 400 of the 650 were “royalists of all varieties”3 and some of the rest Bonapartists. The new National Assembly promptly repealed the “exile law” that had barred members of the royalist dynasties from entering France; as French scholar René Rémond wrote later, “was this not the necessary preface to the restoration of the monarchy?”4

Somehow, amid the chaos of German invasion, civil war, social strife, religious disputes and economic turmoil, France ended up with a republic. And unlike the prior two republics, this one was born not of popular revolution but of elite parliamentary debate that seemed from the state to favor the monarchy. How did this happen?

The simple answer is that the royalists were divided while the republicans were united. Despite their apparent strength, the monarchist majority disagreed on one vital point: who should be crowned king.

One faction, the legitimists, made homage to the Bourbons, the “legitimate” kings of France, the dynasty overthrown in the 1789 and 1830 revolutions. The Bourbon heir, the Comte de Chambord, lived in exile in in Austria and made it clear he was prepared to come home. He also lacked children, normally a drawback for a dynasty but in this case a potential strength, given the divisions among monarchists.

One faction, the legitimists, made homage to the Bourbons, the “legitimate” kings of France, the dynasty overthrown in the 1789 and 1830 revolutions. The Bourbon heir, the Comte de Chambord, lived in exile in in Austria and made it clear he was prepared to come home. He also lacked children, normally a drawback for a dynasty but in this case a potential strength, given the divisions among monarchists.

The other royalist faction, the Orléanists, preferred the rival House of Orléans, descended from King Louis XIV’s younger brother. The Orléanist King Louis Philippe had ruled France in the “July Monarchy” from 1830 to 1848; his grandson Philippe, the Comte de Paris, lived in England (after fighting in the American Civil War on George McClellan’s staff!) and also had a good claim. The Orléanist kings and their supporters were more liberal and bourgeois than the Bourbons; where the Legitimists believed in the intrinsic value of monarchy, the Orléanists saw it more instrumentally as a form of government better suited to protecting order and property than democracy was.

If the two royalist factions could agree on a king, they had the votes to restore the monarchy. And, in fact, the two sides did manage to agree: in a royalist “fusion,” Legitimists and Orléanists agreed that the childless Chambord would become king, and would in turn declare Philippe his heir.

“What their plan did not consider was the obduracy of Chambord,” writes historian Frederick Brown. The Bourbon pretender refused to compromise on many key policies, but perhaps the last straw was a highly symbolic line in the sand: he would only accept the throne if France abandoned the tricolore flag, flown during the Revolution, Napoleon I’s Empire and all governments since 1830, in favor of the white fleur-de-lis of the old regime. This was too much for many royalists: “While eighty die-hard legitimists stood firm behind Chambord, a majority of conservative deputies dissociated themselves from his manifesto.”5

The Orléanists dominated the right, but without the 100-odd Legitimists they didn’t have the majority needed to restore the monarchy. The Legitimists didn’t have the votes to do anything by themselves, but refused to disobey their rightful king and elect another claimant. So the rightist “fusion” split apart. The Orléanists decided to stick with a republic for the time being, “finding revolution and anachronism almost equally objectionable.”6

The monarchist dream wasn’t dead yet: deputies elected a republican president but implied “that France might yet become a monarchy” with references to the country’s “provisional institutions” and yet-to-be-established “definitive institutions.”7

If they couldn’t have a king, they settled for the next best thing: a monarchical president, a 65-year-old general who “assumed, not unhappily, that he was warming the seat for someone else.”8

But the royalists’ moment had passed. As a new constitution was being drafted, right-wing delegates united to vote down every reference to a “republic” — until one reference passed by a single vote, after which “with every subsequent item the majority grew larger.”9

The Legitimists in turn blamed the Orléanist leader, the Duc Du Broglie, for the collapse; “from then on they regularly attacked their former ally, doing damage by any means.”10 In 1874, Légitimists joined with the republicans to bring down an Orléanist government. The next year, when choosing 75 senators-for-life provided for under the constitution, “rather than see men of the Right-Center elected, a group of Legitimists preferred, from resentment and at the risk of compromising the future, to reach an understanding with the Left and elect 57 republicans, leaving only eight seats for the Right-Center.”11

Even as the royalist majority frittered away its chance, the republicans made sure they didn’t blow it — as they had in 1848, in the brief Second Republic. At that time, both liberals and leftists wanted a republican government, and their alliance was able to topple the monarchy. But the radicals continued pressing for more and more societal change — which ended up provoking a backlash from the middle class and peasantry in favor of conservative forces. As historian Mike Rapport writes, “the radicals’ hot-heated behavior” stirred “anxieties over disorder,” which led some supporters of the republic to reconsider. “The political middle ground was crumbling beneath the feet of those republicans who wanted peaceful social reform: compromise between ‘order’ and the ‘social republic’ was becoming dangerously elusive.”12 Moderates joined with conservatives to support a military suppression of a worker uprising, and the volunteers included not just well-to-do bourgeois but “shopkeepers and workers who believed that they were defending their neighborhoods from ‘anarchy’… All those in the French population who felt that they had something to lose were alarmed at the prospect of social disintegration.”13

In contrast, in the 1870s, the French republican movement held together. Leftists under Leon Gambetta set aside their “serious misgivings” and agreed to bide their time under a conservative republic because “government improvised without a constitution was serving those who argued the need for another Napoleon to restore order.”14 Gambetta formed an alliance with Adolphe Thiers — the conservative republican who crushed the Commune of Paris — “that made (Gambetta’s) agenda for social change less ominous to conservatives and (Thiers’) moderation less unpalatable to social reformers.”15

At the 1876 elections Republicans carried 363 seats against only 180 conservatives — and almost half of them were Bonapartists.16 By 1879, republicans controlled the presidency and assembly. Four years later, Chambord died, “and monarchy with him,” Rémond wrote.17 The Third Republic would endure for 70 years, the longest-lasting system of government in French history since the ancien régime — and the same length of time France has preserved republican government since World War II.

Had the monarchists been able to convert their dominance into victory in the 1870s, France would likely have eventually become democratic — the first and second world wars saw the rest of Europe’s monarchies fall or become constitutional. But France’s republican leadership in the late 19th century championed massive changes including secularization, centralization, national public education and suppression of regional languages,18 some or all of which would have been difficult under a different constitutional system. That’s not bad for a government that wasn’t supposed to last more than a few months.

-

Alex Butterworth, The World That Never Was: A True Story of Dreamers, Schemers, Anarchists and Secret Agents (New York: Pantheon Books, 2010), 51. ↩

-

Butterworth, The World That Never Was, 36 ↩

-

René Rémond, The Right Wing in France: From 1815 to De Gaulle, trans. James M. Laux (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1969), 169 ↩

-

Rémond, The Right Wing in France, 172 ↩

-

Frederick Brown, For the Soul of France: Culture Wars in the Age of Dreyfus (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2010), 42 ↩

-

Ibid ↩

-

Brown 42-43 ↩

-

Brown, For the Soul of France, 44 ↩

-

Brown, For the Soul of France, 47 ↩

-

Brown, For the Soul of France, 46 ↩

-

Rémond, The Right Wing in France, 200-201 ↩

-

Mike Rapport, 1848: Year of Revolution (New York: Basic Books, 2009), 196 ↩

-

Rapport, 1848, 210-211 ↩

-

Brown, For the Soul of France, 47-48 ↩

-

Brown, For the Soul of France, 52 ↩

-

Rémond, The Right Wing in France, 201 ↩

-

Rémond, The Right Wing in France, 203 ↩

-

Graham Robb, The Discovery of France: A Historical Geography from the Revolution to the First World War (New York: Norton, 2007), 324-330 ↩