Alphabétisation

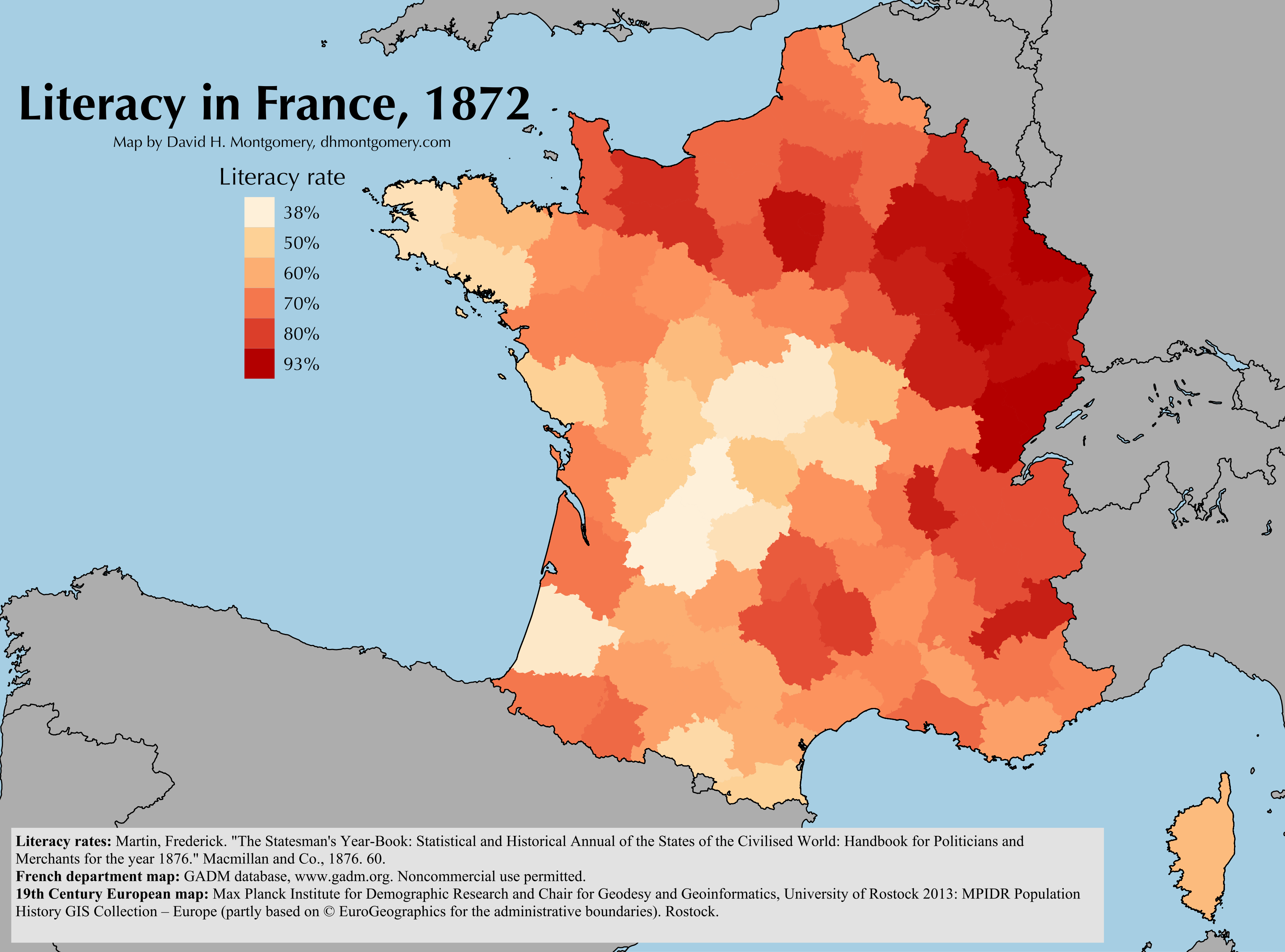

While researching historical elections this week for a future blog post, I stumbled across a fascinating piece of data: a table from an 1876 almanac summarizing the literacy rates in each of the 87 French départements at the time. The results varied wildly, from near-universal literacy in Paris and the country’s industrial northeast to majority illiteracy in the interior of La France profonde.

“The census of 1872 showed an extraordinary difference in the degree of education between the 87 departments of France, the percentage of ignorance ranging between six and sixty,” wrote Frederick Martin in The Statesman’s Year-Book: Statistical and Historical Annual of the States of the Civilised World: Handbook for Politicians and Merchants for the year 1876.

While the northeastern corner of France is a dense cluster of strong education, there are other pockets of literacy as well. “Some regions that were supposed to be far from the light of civilization turned out to have surprisingly high rates of literacy,” writes Graham Robb in The Discovery of France: A Historical Geography from the Revolution to the First World War. By 1830, ”many Alpine villages had been running their own schools for decades.”

Overall about 30 percent of the French population over 6 years old was unable to read or write. In the United States at that time, the illiteracy rate at 14 or up (a different, more generous threshold) was about 20 percent — and about 10 percent if one excluded African-Americans, many of whom had been forbidden by law to read or write less than a decade before. (The French illiteracy rate was higher among adults over 20, at 33 percent, than it was among children 6 to 20, at 24 percent, so I’m not sure how much the different age cutoffs between the French and American censuses matters.)

Hurting the French literacy rate was the aftermath of the 1870-71 Franco-Prussian War, which saw France forced to cede several northeastern provinces to the new country of Germany. These provinces, as can be inferred from the map, had very high literacy rates.

“In the departments now constituting the German ‘Reichsland’ of Alsace-Lorraine, France lost the most educated portion of her former inhabitants,” Martin wrote. “The progress of education indicated in the census returns of 1866 and 1872 was very slight, due to some extent to the loss of these provinces.”

(This census in question was taken during the time of the French political conflicts I wrote about in March in “The Accidental Republic” — a post whose sources also inform this analysis.)

View a table of the data here.

Martin left no doubt as to who he blamed for the woeful state of affairs in some parts of France, inserting this table in a section titled “Church and Education.”

Public education in France is entirely under the supervision of the Government, and to a great extent, partly directly, but more indirectly, in the hands of the Roman Catholic clergy. The duration of school life is usually regulated by the religion of the scholar. Roman Catholics of the lower classes, more particularly in the rural districts, rarely visit school after eleven or twelve, the age at which they receive their first communion, while Protestants commonly remain at school until about 16. The elementary schools, superintended by the clergy, impart a very defective education.

This was the case even though French law had ostensibly required every community of 500 people or more to establish a school for boys since 1833 — though such a school could be private or public. (Girls’ schools were mandated in 1867.) “Many village teachers had been little more than skivvies: they helped the priest at mass, rang the bells, sang in the choir and were paid the same as a day-labourer, sometimes more if they could read and write,” Robb writes (emphasis added).

But Robb notes that the inadequacies of church-led education weren’t solely to blame for disparate education:

Many parents were reluctant to send their sons and daughters to school when they needed them for the harvest. Inspectors often found that girls were kept out of school to work as seamstresses in filthy sweatshops where they spent the day with relatives and neighbors, learning the local traditions and values that their mothers considered to be a proper education. Above all, many parents were afraid that once they learned to speak and write French like Parisians, their children would leave for the city and never come home.

“Their fears were justified,” Robb noted. As the new republican government nationalized education, “the eradication of (local dialects) became a cornerstone of education policy” — as was eradicating what the republican leaders saw as “superstitions” but locals saw as core parts of their Catholic faith.

Sharing Martin’s distaste for the church role in education, French education minister Jules Ferry expelled the Jesuit schoolteachers from France in 1880. The next year he passed a law establishing free, government-supported education, and in 1881 another secularizing the education system.

This was, to say the least, extremely controversial.

“All over France,” writes Frederick Brown in For the Soul of France: Culture Wars in the Age of Dreyfus, “teachers holding diplomas from normal schools locked horns with the local curate.”

“The spirit of Satan, embodied in the revolution, is successfully striving to obliterate what remains of centuries-old traditions and the religious institutions to which our country owes its past greatness,” France’s leading Catholic newspaper wrote. It regularly described schoolteachers as “professors of atheism,” “masters of demagogy,” “seasoned revolutionaries” and “missionaries of the modern mind.”

In one school in Lozère (a department with an illiteracy rate of just 20 percent), a priest denounced the schoolteacher for reading from a history text in “in which Joan of Arc was described as ‘believing’ that she had heard voices. ‘He insisted that I use another text,’ wrote the teacher.’

I replied that it was impossible to do so. “Well then, it’s war between the Church and the School,” he said. And war it was. He attacked me all year long, every week, in a Catholic paper called La Croix de la Lozère. My personal and professional life offered endless pretexts to spit venom.”

In one vivid example of the battle’s severity, the teacher on one day found the schoolhouse door smeared with excrement.

The process of education was a slow one. Despite an overwhelming emphasis on using the new public schools to cultivate French nationalism, “on the eve of the First World War, about half of all recruits, and quite a few future officers, were unaware that France had lost territory to Germany in 1870,” Robb writes. “Alsace and Lorraine might as well have been foreign countries.”

But eventually the regional languages would be largely suppressed, “the majority of French people became French-speakers,” and literacy spread, too. To a certain extent, it wasn’t the controversial schools but another national institution that finally convinced rural families to embrace education: the army.

“Parents suddenly felt the burden of illiteracy,” Robb wrote, “when their sons left home and letters arrived home from the regiment, written by a comrade — with rude words and dirty stories if the comrade had a nasty sense of humour — and were read out on the doorstep by the postman.”