Bad omens

In their post-apocalyptic comedy novel “Good Omens,” authors Terry Pratchett and Neil Gaiman describe the nefarious handiwork of the demon Crowley, an agent of Hell on Earth with a particularly acute grasp of human nature:

Many phenomena — wars, plagues, sudden audits — have been advanced as evidence for the hidden hand of Satan in the affairs of Man, but whenever students of demonology get together the M25 London orbital motorway is generally agreed to be among the top contenders for Exhibit A.

Where they go wrong, of course, is assuming the wretched road is evil simply because of the incredible carnage and frustration it engenders every day.

In fact very few people on the face of the planet knew that the very shape of the M25 forms the sigil odegra in the language of the Black Priesthood of Ancient Mu, and means: “Hail the Great Beast, Devourer of Worlds.” The thousands of motorists who daily fume their way around its serpentine lengths have the same effect as water on a prayer wheel, grinding out an endless fog of low-grade evil to pollute the metaphysical atmosphere for scores of miles around.

It was one of Crowley’s better achievements. It had taken years to achieve, and had involved three computer hacks, two break-ins, one minor bribery and, on one wet night when all else had failed, two hours in a squelchy field shifting the marker pegs a few but occultly incredibly significant meters. When Crowley had watched the first thirty-mile-long tailback he’d experienced the lovely warm feeling of a bad job well done.

Remembering this passage now as I live in St. Paul — just an hour away from Gaiman’s current home in Menomonie, Wisconsin — has me fixated on one thought: Did Crowley ever pay a visit to Minnesota during the planning of the downtown intersections of Interstate 94 with Interstates 35E and 35W?

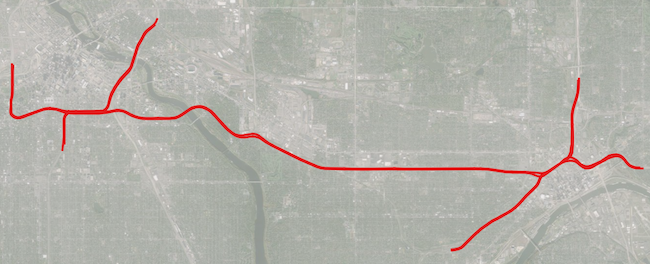

I-94 doesn’t merely intersect with its north-south cousins in downtown Minneapolis and downtown St. Paul, but it actually merges with them for one-mile stretches through the densest parts of the 3.8 million-resident metropolitan area. The concurrences cause miles-long back backups every rush hour as cars are funneled together and then yanked apart, with a significant portion of those cars attempting to cross multiple lanes of traffic to continue on their planned routes. Moreover, it’s actually impossible to make certain direct exchanges — shifting from eastbound I-94 to southbound I-35E, for example — without leaving the interstate altogether and using side roads.

I’m sure there are reasonable spatial and financial reasons for constructing the mergers this way, and even a perfectly designed interchange would have rush hour backups from the sheer traffic volume — as some other merger-less Twin Cities interchanges do. But still: my hypothesis remains the devil’s hand at work.