Planting seeds of journalism and defeat

Almost eight years ago to the day, Hillary Clinton’s campaign in the vital caucus state of Iowa shot itself in the foot. I helped pull the trigger.

It was early November, and Clinton was still the frontrunner for the Democratic nomination. But in retrospect she had already begun the decline that saw her finish a shocking third place in the Iowa caucuses, and thus the decline that saw her lose the nomination to an Illinois senator named Barack Obama. On Oct. 30, Clinton had stumbled badly in a national debate when she waffled on the question of driver’s licenses for undocumented immigrants. On Nov. 10, Obama would deliver an acclaimed speech at the Iowa Jefferson-Jackson Day Dinner that helped accelerate his Iowa campaign.

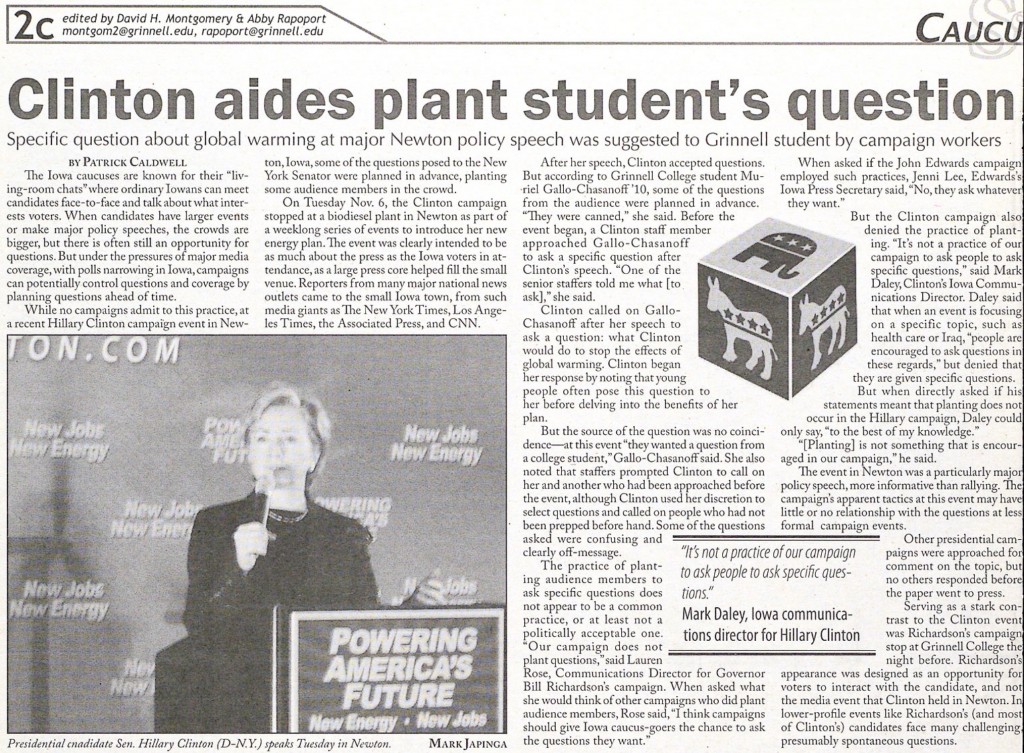

In between, on Tuesday, Nov. 6, Clinton visited Newton, Iowa, and called on a 19-year-old Grinnell College sophomore named Muriel Gallo-Chasanoff, who asked a question about her approach to climate change.

Also at the event was a reporter for the Scarlet & Black, the Grinnell student newspaper, of which I was co-editor. The reporter, Pat Caldwell, naturally interviewed Gallo-Chasanoff about her experience getting to ask Clinton a question, but got way more than she bargained for: Gallo-Chasanoff mentioned off-handedly that a Clinton staffer had given her the question to ask.

“I said ‘Yeah, can I ask how her energy plan compares to the other candidates’ energy plans?’” Gallo-Chasanoff later told CNN about the incident. Instead, she told CNN, the staffer said Clinton might not be familiar with the other candidates’ plans, and instead opened a binder to a page with more than a half-dozen questions on it. The top question, which said “college student” in brackets, read: “As a young person, I’m worried about the long-term effects of global warming. How does your plan combat climate change?”

Caldwell immediately recognized the news in Gallo-Chasanoff’s off-handed mention of the planted question, but tried to play it cool to avoid spooking her in the middle of the interview.

The scramble

But things didn’t come together easily. Clinton representatives on campus quickly pushed back on the story, and they successfully got to Gallo-Chasanoff. A few hours after talking to Caldwell, she emailed him to try to put the genie back in the bottle:

“im feeling a little uncomfortable about the whole planted questions thing so i’d really appreciate it if you would talk to emily or jordan about it first and please respect whatever wishes they have regarding the info,” Gallo-Chasanoff wrote to Caldwell in an email. She later told CNN that “a Clinton intern spoke to her to say the campaign requested she not talk about the story to any more media outlets and that if she did she should inform a staffer.”

“Emily” and “Jordan” were the on-campus leaders of the Clinton campaign. Caldwell, myself and co-editor-in-chief Abby Rapoport agreed quickly that we weren’t going to defer to the Clinton campaign’s wishes and forged ahead.

As Rapoport took the lead in working with Caldwell, I tackled another problem: at this very moment, the Scarlet & Black was in the middle of a long-overdue website overhaul. The paper’s old site had become essentially nonfunctional, and for some time we had only uploaded PDF versions of the paper. If individual articles were posted at all, they went onto a free Blogspot blog. We had hired a student, Saugar Sainju, to build us a new website, but the project wasn’t supposed to be done for a few more weeks.

I emailed the Sainju with the subject line “Urgent—web site”:

We're going to have a major story coming out in this Friday's issue. It's political and will probably attract a lot of traffic from political sites. We'd like to have this coming to our web site, rather than the blog or a third party site. Is there any way we can rush the web site, or at least one particular article, up by Friday afternoon? This would automatically kick in that extra bonus I talked about--$750 for the job.

For the bonus, he agreed to rush the job. (Though neither of us are quite sure, I believe the $750 was the total cost for the job, not the bonus. Our paper had limited budgets.)

The article continued to face difficulties. We couldn’t track down a Clinton spokesperson to get the response the story needed — though the other Iowa campaigns responded quickly to our vaguely worded inquiries about planted questions, seemingly worried that the story might have been about them. On-campus Clinton leaders met with us to try to kill the story. We were starting to feel nervous about the story as our deadline approached.

All this time, the staff still had to produce the regular paper by Thursday night — 20 pages long including a special section on mental health on campus, while juggling our normal class schedules. (At Grinnell, the Scarlet & Black has no academic affiliation, so students work on it like a campus job while taking a full courseload.) Even before the Clinton article arose, both Features and Sports had planned articles fall through, necessitating a scramble to fill the vacated space. Moreover, Caldwell was the Features editor, responsible for editing and designing a section of the paper in addition to writing his story. Rapoport stepped in to handle his editing duties.

Finally, late Thursday evening, the Clinton campaign got back to us. Their response didn’t just give us the quote we needed for the story — it also helped quell our fears. Clinton’s Iowa communications director drove from a small town into cell phone range to try to talk Caldwell into not running the story, but his tone immediately made it clear that this had actually happened. The Clinton spokesperson ducked Caldwell’s questions, giving him only the non-denial that “It’s not a practice of our campaign to ask people to ask specific questions.” We finished the story Thursday night — really into Friday morning — and got a few hours of sleep.

By midday Friday, our web designer finished the new template to upload the planted-questions story (and one other article, just so it didn’t look like we had made the website just for this one article, even though we had). Rival campaigns made sure that political media got the story, and suddenly the Scarlet & Black was at the center of the a national media frenzy.

The aftermath

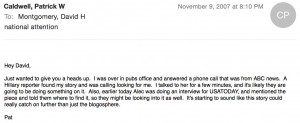

By Friday evening, Caldwell had been deluged with requests from national reporters wanting to interview him as a part of the story. He emailed me at 8:10 p.m. with the subject “national attention.”

“Just wanted to give you a heads up,” he wrote. “I was over in pubs office and answered a phone call that was from ABC news. A Hillary reporter found my story and was calling looking for me. I talked to her for a few minutes, and it’s likely they are going to be doing something on it… It’s starting to sound like this story could really catch on further than just the blogosphere.”

“Just wanted to give you a heads up,” he wrote. “I was over in pubs office and answered a phone call that was from ABC news. A Hillary reporter found my story and was calling looking for me. I talked to her for a few minutes, and it’s likely they are going to be doing something on it… It’s starting to sound like this story could really catch on further than just the blogosphere.”

At 2:16 a.m. Saturday morning — we were college students — our copy editor emailed with the headline “We did it!” to note that Fox News had published a story about the planted question in which they got the Clinton campaign to admit planting the question (though Fox referred to the college as “Grinnell University”).

Caldwell ultimately did a national television interview from our paper’s office. Our student newspaper story was the lead link on the Drudge Report for two days, which made us glad that the college’s robust servers were hosting our content.

I wrote a story for the next week’s S&B about the national reaction — which led to one of my more embarrassing moments as a journalist. I did a phone interview with Major Garrett, then Fox News’ Obama beat reporter, but a day after the interview my computer’s hard drive crashed. I lost the interview notes and was forced to beg for a do-over interview — which I never ended up getting. As student newspaper reporter I was lucky to get one interview with a national figure; I wasn’t going to get a second chance.

For Clinton, the incident stung. A story about planting questions would be bad for any campaign. But like Clinton’s driver’s license answer, the planted questions story was particularly damaging for Clinton because it reinforced a narrative about her: that she would say or do anything to get elected.

Would Clinton have still lost the Iowa caucuses without a controversy about planted questions? Almost certainly. But it didn’t help, another cut in a steady diet of bad news Clinton endured in the months leading up to the Iowa caucuses.

In addition to the statewide repercussions, the planted question story had local impact, too. For months before the story, the Clinton campaign had been preparing for an as-yet-unscheduled campaign visit by Clinton to the Grinnell College campus. After the planted question story, all that talk suddenly stopped. Clinton never did campaign at Grinnell College, a center of Democratic caucus goers — possibly to avoid reviving an embarrassing campaign incident. (Her husband, former president Bill Clinton, did give a speech on her behalf, though he didn’t take media questions at the event.) All the other major Democratic candidates that year made at least one stop on campus.

That hurt Clinton come caucus day, when her supporters were humiliatingly blown out of the water at the on-campus caucus — earning no delegates and finishing behind not just Obama and John Edwards but also then-Sen. Joe Biden, who would drop out of the race after the Iowa Caucuses.

But time heals all wounds. Yesterday, on Nov. 3, 2015, Hillary Clinton finally visited Grinnell College for a rally eight years after a planted question nearby contributed to her loss of the nomination. Her town hall event focused on gun control and the minimum wage and apparently included no references to the 2007 planted question incident.

The journalism

But the story definitely would never have broken without the Scarlet & Black, and for that, I’ll always be proud, even though I was just an editor on the story, not the writer. It was the first real major scoop I was ever involved with as a journalist.

We didn’t get the scoop through any hard-core Woodward-and-Bernstein investigations, but because our reporter was trying to write a small-bore, hyper-local story for the campus newspaper about a student who got to ask a question to a presidential candidate. A national reporter, following a candidate around in case they make news and listening to them give the same stump speech and take similar questions at event after event, might have never gone to the trouble of talking to the girl who asked about global warming. Were I covering such an event today, I probably wouldn’t have.

Many of the key players in this incident have continued in journalism. I stayed in political reporting after graduation, in South Dakota for six years and now for the St. Paul Pioneer Press. Caldwell went on to write for The American Prospect and Mother Jones, while Rapoport wrote for the Texas Tribune, the Texas Observer and the Prospect.

Sainju stayed in web development, and said the rush job to finish the S&B’s website for this story was a key element on his resume early on and helped establish him in the field.

Ironically, looking back on this first big scoop with the eye of an experienced journalist, we made a lot of mistakes. The article backed leisurely into the planted question issue with a discursive lede about the nature of the Iowa caucuses, instead of a straight news lede (“Hillary Clinton’s presidential campaign planted a question with a Grinnell College student at a Tuesday event in Newton”) or an anecdotal lede (“Muriel Gallo-Chasanoff ‘10 got a brush with fame Tuesday when presidential frontrunner Hillary Clinton called on her to ask a question at a Newton rally. But Gallo-Chasanoff’s question about climate change didn’t come from the second-year student. Instead, a Clinton aide gave her the pre-written question, Gallo-Chasnoff said.”).

More glaringly, we totally buried the story in our print edition. The lead article in the Nov. 9, 2007 Scarlet & Black was about the annual “Love Your Body Week” event — likely chosen because it had the best photo of any of our news stories that week — while additional stories covered on-campus events including assaults at a Halloween party, the hiring of a new dean and the travails of a proposed campus drug policy.

More glaringly, we totally buried the story in our print edition. The lead article in the Nov. 9, 2007 Scarlet & Black was about the annual “Love Your Body Week” event — likely chosen because it had the best photo of any of our news stories that week — while additional stories covered on-campus events including assaults at a Halloween party, the hiring of a new dean and the travails of a proposed campus drug policy.

The Clinton story appeared on the 10th page of the paper, in a special section devoted to Iowa Caucus stories. We did tease the story on the bottom of the front page — but again in an oblique, backwards manner: “Are presidential campaigns planting questions in the audience at events?” asked the third of four “Inside this S&B” teasers at the bottom of the page.

But despite all that students apparently did manage to find it. Don Smith, a professor emeritus at Grinnell and at the time the chair of the local county Democrats, told Guardian reporter (and 2006 Grinnell alum) Ben Jacobs that the planted question story “may have cut back on student support” for Clinton — either directly, or by keeping her from doing a campus rally that might have garnered more supporters.

Despite our placement of the story in print, we knew the planted question story would be bigger national news than it was locally. Our focus had been on getting the story online, rather than splashing it over the front of the paper. Were I in charge today, I’d have made sure to lead the paper with the Clinton article. But I didn’t feel bad at the time about its placement. It was a learning experience as a journalist, and having been free to make mistakes like our placement of the Clinton story helped make me into the reporter I am today.