The map in the painting

This post is adapted from a series of tweets I made on May 2, 2018.

This is a famous painting by Francis Bicknell Carpenter, “First Reading of the Emancipation Proclamation by President Lincoln”:

It depicts the moment when President Abraham Lincoln presented a draft of the Emancipation Proclamation, which used the president’s war powers to free all slaves held in rebellious areas of the United States, to his cabinet. You can see Lincoln, along with prominent cabinet members such as Treasury Secretary Salmon P. Chase (standing at left) and Secretary of State William Seward (seated at right, facing Lincoln).

The painting also has nearly as many documents as it does people. There are two pages of the Proclamation itself, one in Lincoln’s hand and the other on the table. There’s a map in the lower left, and another on the table at center-right.

But focus for a moment on the lower right hand corner of the painting. There’s a map, half-seen, leaning up against a table leg, showing the southern United States (then currently in rebellion).

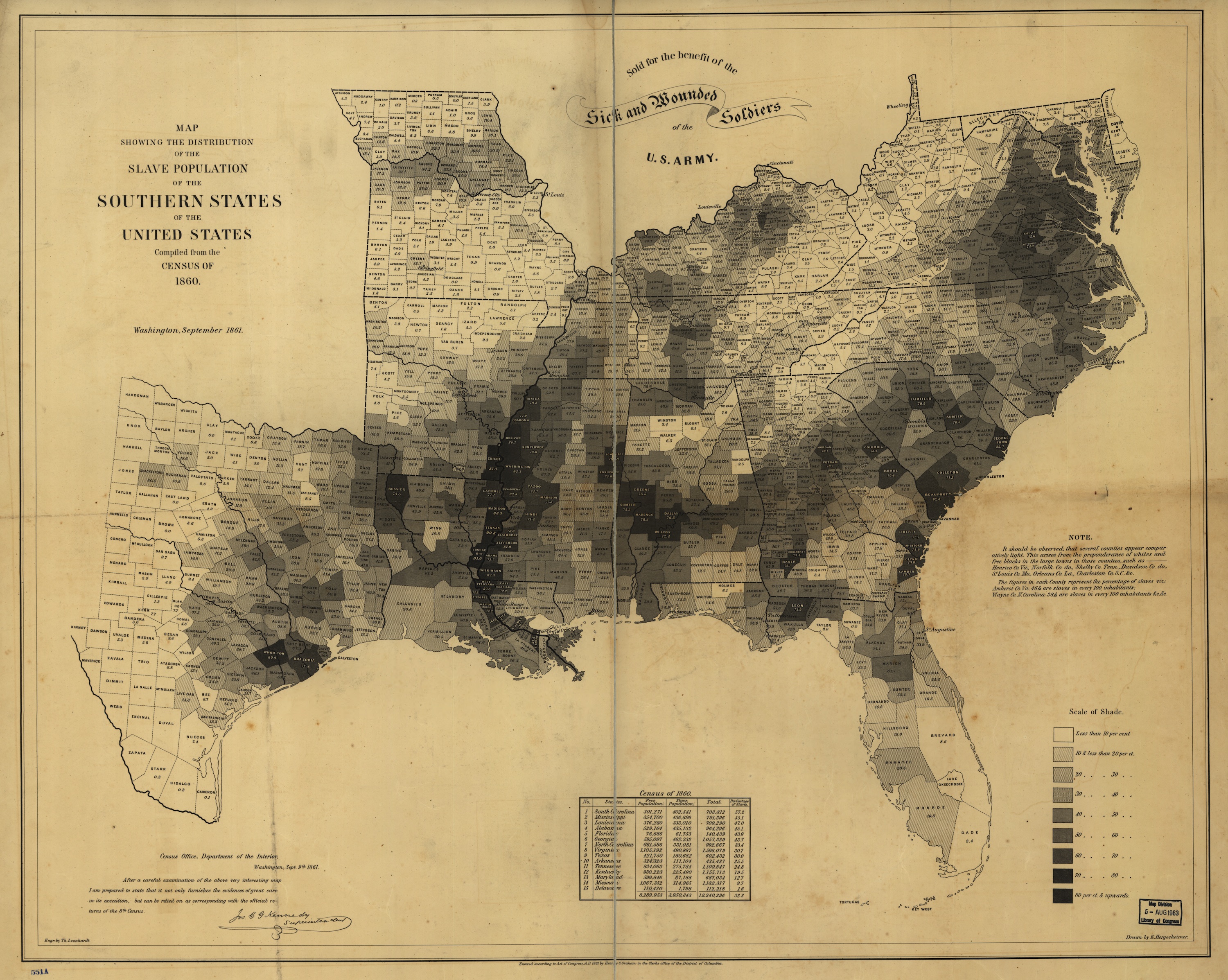

That’s not just an artist’s embellishment. It’s a rendition of a real, and very important, map: “Map Showing the Distribution of the Slave Population of the Southern States of the United States,” from the 1860 Census, by Edwin Hergesheimer:

We’re used to maps like that today, that show data on the map by use of shading or coloring. But in 1861, that was still relatively new. That type of map, now called a “choropleth map”, was invented in 18261 and only became popular in the years leading up to the Civil War.

Hergesheimer’s map simply reproduced the results of the 1860 U.S. Census, which calculated for each county the total number of free individuals and the total number of enslaved individuals.

What made this such a brilliant map and data visualization was that it didn’t just represent data geographically, but it represented important geographic trends.

Looking at this map, you can see the highest concentration of slaves in South Carolina, Mississippi, Louisiana, and Alabama. The order of secession from the U.S.: South Carolina, Mississippi, Florida, Alabama, Georgia, Louisiana. So this map, intentionally or not, weighed in on a political debate at the time (that hasn’t entirely died down): was the Civil War primarily about slavery or state’s rights? This map suggested the former. (So do the states’ actual slavery-heavy stated reasons for secession.)

You can also see some exceptions to the trends. Western Virginia —what would soon become the separate state of West Virginia — has very few slaves. So does Eastern Kentucky. Missouri and Maryland have slaveholding pockets but otherwise have few slaves.

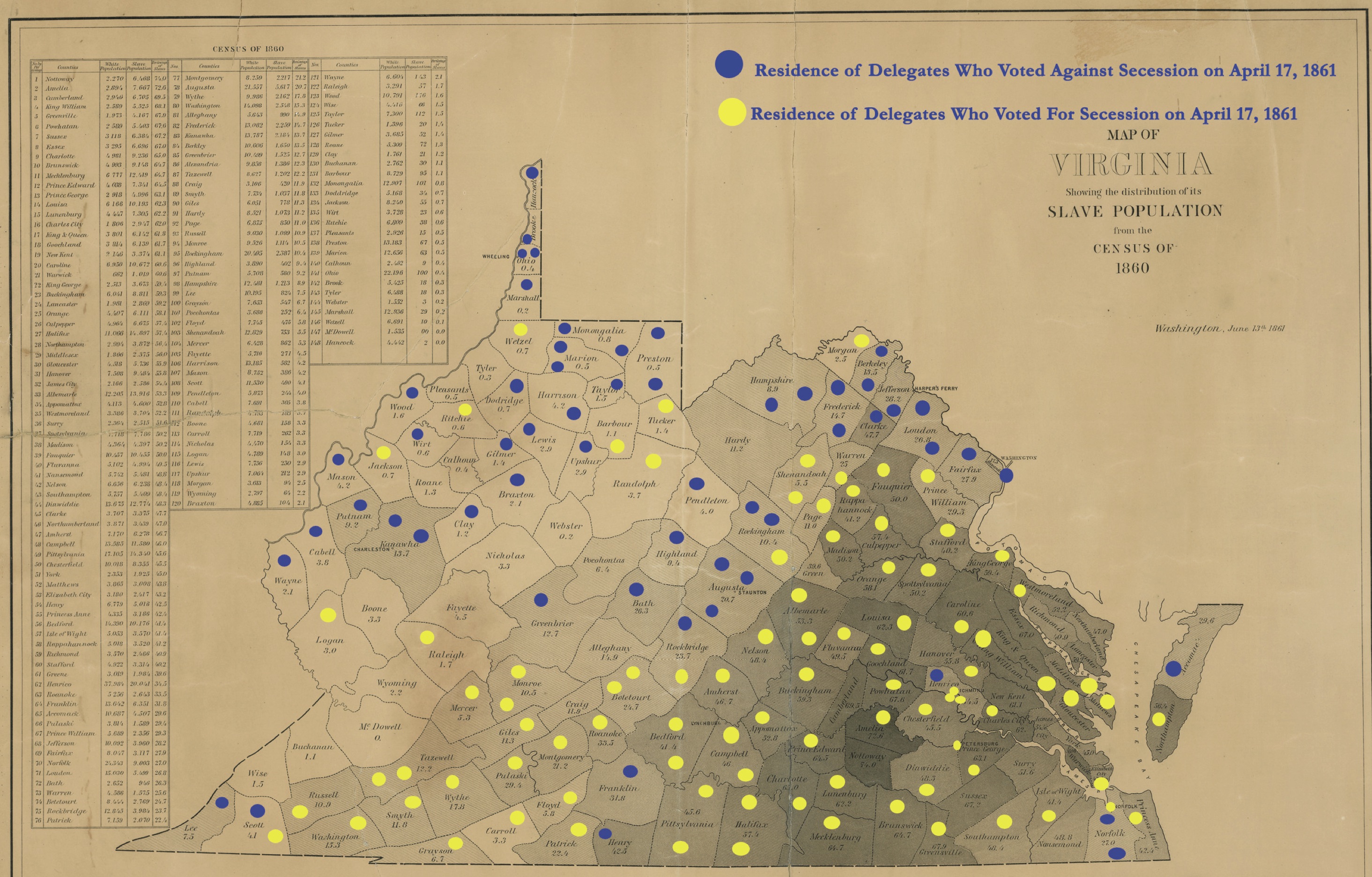

The cartographer, Hergesheimer, did a similar map for just Virginia. Here someone2 has overlaid how delegates voted in Virginia’s 1861 secession convention:

There are exceptions to the pattern, but the pattern itself is unmistakable.

As important as the Hergesheimer map is to us today as a historical tool to understand slavery and the Civil War, however, it was also important at the time of the Civil War itself.

Carpenter, who painted “First Reading of the Emancipation Proclamation by President Lincoln,” lived at the White House for six months while working on his painting. Lincoln let him convert the White House’s State Dining Room into a studio for the duration of his stay.

During that time, Carpenter repeatedly saw the president studying the map. He put it in the painting because it was important to Lincoln, as well as being important generally.

Carpenter actually surreptitiously borrowed the map to try to capture it for his painting. A few days later, Lincoln walked into his studio and said, “You have appropriated my map, have you? I have been looking all around for it.” Then he put on his glasses and began looking at it again.3

Lincoln called it his “slave map.” He liked it because it showed the South wasn’t monolithic. And he used it to track the progression of Union military incursions into the South.

After Lincoln began looking at his map again in Carpenter’s studio, in early 1864, he immediately pointed out the location of a recent cavalry raid into Virginia by Judson Kilpatrick, a Union General.

“It is just as I thought it was,” Lincoln said, pointing to Kilpatrick’s position. “He is close upon — County, where slaves are thickest. Now we ought to get a ‘heap’ of them, when he returns.”4

Lincoln had also used the raw data on slave population from the 1860 Census to calculate the feasibility of “compensated emancipation” — paying slaveowners for the loss of their slaves. He may have used this map for that, too. But by 1863 Lincoln had abandoned the idea of compensated emancipation — as the fact that this map features in a painting about the Emancipation Proclamation shows.5

Instead, the map was now being used to follow — and possibly to direct — military incursions to liberate slaves by force.

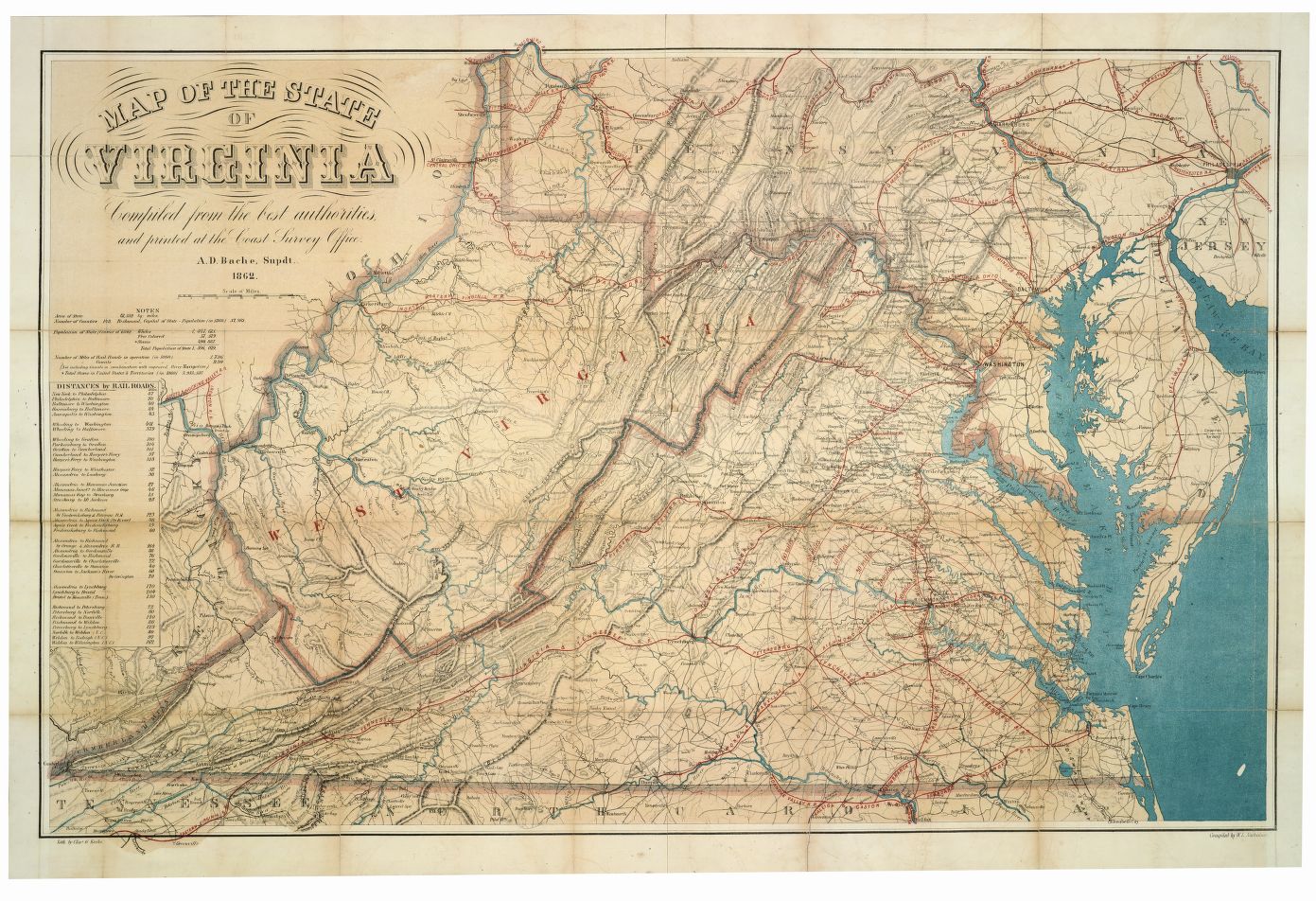

This minor detail — a map in the corner of a painting — shows not just the power of maps to understanding history, but how important they’ve been throughout history. In fact, it’s not even the only map in the painting! Less prominently displayed, on the table behind Seward, is another popular Civil War map: the Coast Survey’s “Map of the state of Virginia”:

That map includes roads and railroads and has concentric circles around Richmond. Scholar Susan Schulten reports that the Coast Survey sold more than 5,000 copies during the war, as generals and ordinary people alike sought to understand the conflict.6

The painting

Carpenter’s use of maps isn’t the only interesting thing about his painting. He was a supporter of the Emancipation Proclamation who asked to make his painting because of “an intense desire to do something expressive of… appreciation of the great issues involved in the war.”

The long-prayed-for year of jubilee had come; the bonds of the oppressed were loosed; the prison doors were opened… Surely Art should unite with Eloquence and Poetry to celebrate such a theme.”7

The composition in Carpenter’s painting is deliberate. Seated to Lincoln’s right (our left) are Secretary of War Edwin Stanton and Chase, the Treasury Secretary, who Carpenter identified as supporters of the Proclamation; on the other side of the table were cabinet members more skeptical of the document.8 This had the advantage, if Carpenter is to be believed, of roughly matching where each man sat relative to Lincoln during the meeting.

The composition in Carpenter’s painting is deliberate. Seated to Lincoln’s right (our left) are Secretary of War Edwin Stanton and Chase, the Treasury Secretary, who Carpenter identified as supporters of the Proclamation; on the other side of the table were cabinet members more skeptical of the document.8 This had the advantage, if Carpenter is to be believed, of roughly matching where each man sat relative to Lincoln during the meeting.

But the details of the Proclamation’s reading were murkier than Carpenter’s framing. Most members of the cabinet opposed issuing the Emancipation Proclamation at this first meeting.

Stanton did indeed support it, having “instantly grasped the military value,” historian Doris Kearns Goodwin writes.

Surprisingly, so too did Edward Bates, the conservative attorney general seated at far right — though Bates’ support was based on the idea that the freed slaves would be forcibly expelled back to Africa.

Bates “had long favored gradual emancipation,” Goodwin writes in “Team of Rivals,” but “if the president’s proclamation could bring the war to a speedier conclusion, he would give it his ‘very decided approval.’”9

If Bates surprised the cabinet with his support of the proclamation, Chase surprised with his opposition to it. Chase had been a lifelong and vehement abolitionist, but now he argued Lincoln was moving too fast and backed a “quieter, more incremental approach.”

Goodwin argues that Chase, who harbored presidential ambitions, opposed the proclamation for selfish political reasons — it could undercut Chase’s strength vs. Lincoln among the radical faction of the Republican Party.10

Seward, the secretary of state, argued against the proclamation, fearing it could “provoke a racial war in the South so disruptive to cotton that the ruling classes in England and France would intervene to protect their economic interests.” (In fact, Seward’s intuition was exactly backwards: the Emancipation Proclamation ultimately ended up bolstering support for the Union in Europe, where slavery was seen as “an evil demanding eradication.”)

But once he saw Lincoln was committed, Seward “was steadfast in his loyalty.” His only objection was on timing: he urged Lincoln to wait until after a victory to issue the proclamation.

“The wisdom of the view of the Secretary of State struck me with very great Force,” Lincoln told Carpenter. “It was an aspect of the case that, in all my thought upon the subject, I had entirely overlooked.” Lincoln ended up waiting until after the Battle of Antietam, a technical Union victory, to issue the proclamation.11

Carpenter’s painting actually reflects the moment when Seward made his concerns known. Notice how the cabinet is looking not at Lincoln or the document, but off-center at Seward.

“To the Secretary of State, as the great expounder of the principles of the Republican party… would the attention of all at such a time be given,” Carpenter wrote.

Though the people in the painting are looking at Seward, the light and color highlights the Emancipation Proclamation itself — a shining point of light in an otherwise dimly lit room.

Though the people in the painting are looking at Seward, the light and color highlights the Emancipation Proclamation itself — a shining point of light in an otherwise dimly lit room.

The left side of the painting — where Carpenter positioned the cabinet members he saw as supporters of emancipation — is lighter than the right side, where the skeptics and opponents sit.

Off-center, but at the center, is Lincoln. “There were two elements in the Cabinet–-the radical and the conservative,” Carpenter wrote. Mr. Lincoln was placed at the head of the official table, between two groups, nearest that representing the radical; but the uniting point of both.”

A few other grace notes in the painting: the painting on the wall at the center is Andrew Jackson, who was a slaveholder but also a fierce opponent of secession. At left is a painting of Simon Cameron, a former member of the cabinet, now resigned under a cloud of scandal. Cameron had been secretary of war. Despite having resigned, Carpenter puts him at the scene indirectly, via a hung painting, behind his successor.

Finally, there is a sheathed sword leaning against the chair between Seward, Bates and Hergesheimer’s map. This was actually a late addition to the painting, made on the eve of the painting’s unveiling in 1878 — a representation of the sword of Confederate General David E. Twiggs, presented to him for his Mexican War heroism but then, after Twiggs turned traitor at the outset of the Civil War, seized after the Union capture of New Orleans and sent to Lincoln.12 After learning that Lincoln had possessed this captured sword, Carpenter added it as a “symbol of Confederate submission” — painting it over another, less interesting sword that he had added just the week before.13

(This post has been updated on Sept. 11, 2019 to add details about the sword.)

Sources

- Allen, Erin. “Mapping Slavery.” Library of Congress Blog, Oct. 31, 2012.

- Carpenter, Francis. Six Months at the White House with Abraham Lincoln New York: Hurt and Houghton, 1866.

- “First Reading of the Emancipation Proclamation of President Lincoln.” Wikipedia. Retrieved May 4, 2018.

- Goodwin, Doris Kearns. Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham Lincoln. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2005.

- “Map of April 17, 1861, Vote on Secession.” Library of Virginia.

- “Mapping Slavery in America.” University of Chicago Press.

- Onion, Rebecca. “The Map That Lincoln Used to See the Reach of Slavery.” Slate, Sept. 4, 2013.

- Schulten, Susan. Mapping the Nation: History and Cartography in Nineteenth-Century America. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2012.

-

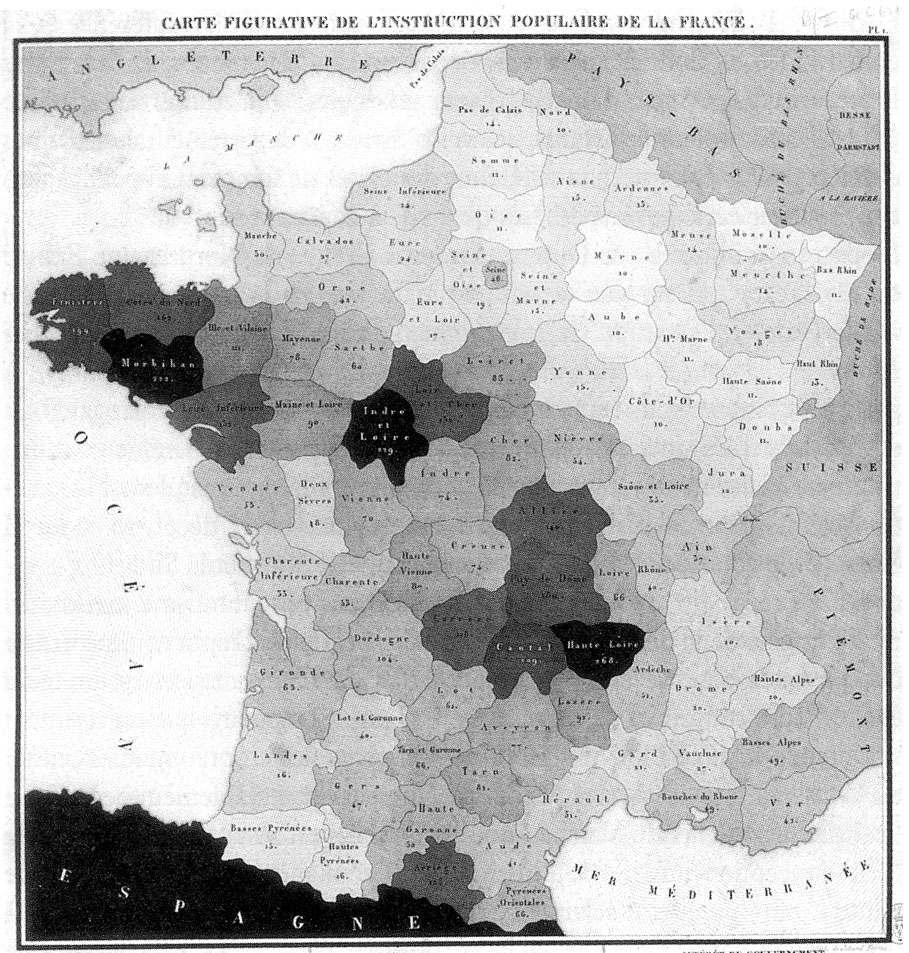

The choropleth map was invented in 1826 by a French economist, Charles Dupin, for a map showing the percentage of French boys who attended school (right). Dupin made moral and economic arguments about this: “The Treasury Department collects 6,820,000 fr. in land taxes from enlightened France, and 3,599,700 from dark France,” he estimated. For more on French literacy and education in the 19th Century, read my essay “Alphabétisation”, which includes my own choropleth map, of French literacy rates in the 1870s. ↩

The choropleth map was invented in 1826 by a French economist, Charles Dupin, for a map showing the percentage of French boys who attended school (right). Dupin made moral and economic arguments about this: “The Treasury Department collects 6,820,000 fr. in land taxes from enlightened France, and 3,599,700 from dark France,” he estimated. For more on French literacy and education in the 19th Century, read my essay “Alphabétisation”, which includes my own choropleth map, of French literacy rates in the 1870s. ↩ -

“Map of April 17, 1861, Vote on Secession.” Library of Virginia. ↩

-

Abraham Lincoln was delightful. ↩

-

Susan Schulten. Mapping the Nation: History and Cartography in Nineteenth-Century America, 142. Kilpatrick was a controversial figure at the time. He was nicknamed “Kill-Cavalry” for the high casualty rates he suffered, and the raid Lincoln was following on his “slave map” ended up as a debacle when one of Kilpatrick’s subcommanders got separated and killed along with a copy of his orders. Despite this disgrace, William T. Sherman chose Kilpatrick as a cavalry commander for his famous Atlanta campaign. “I know that Kilpatrick is a hell of a damned fool, but I want just that sort of man to command my cavalry on this expedition,” Sherman said. ↩

-

Francis Carpenter. Six Months at the White House with Abraham Lincoln, 12. ↩

-

Doris Kearns Goodwin. Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham Lincoln, 465. ↩

-

Goodwin, 467. ↩

-

Goodwin, 467-8. ↩

-

See Morphy Auctions. ↩

-

Martin A. Sweeney, Lincoln’s Gift from Homer, New York: A Painter, an Editor and a Detective, 125. ↩