The 19th Century opponents of the Electoral College

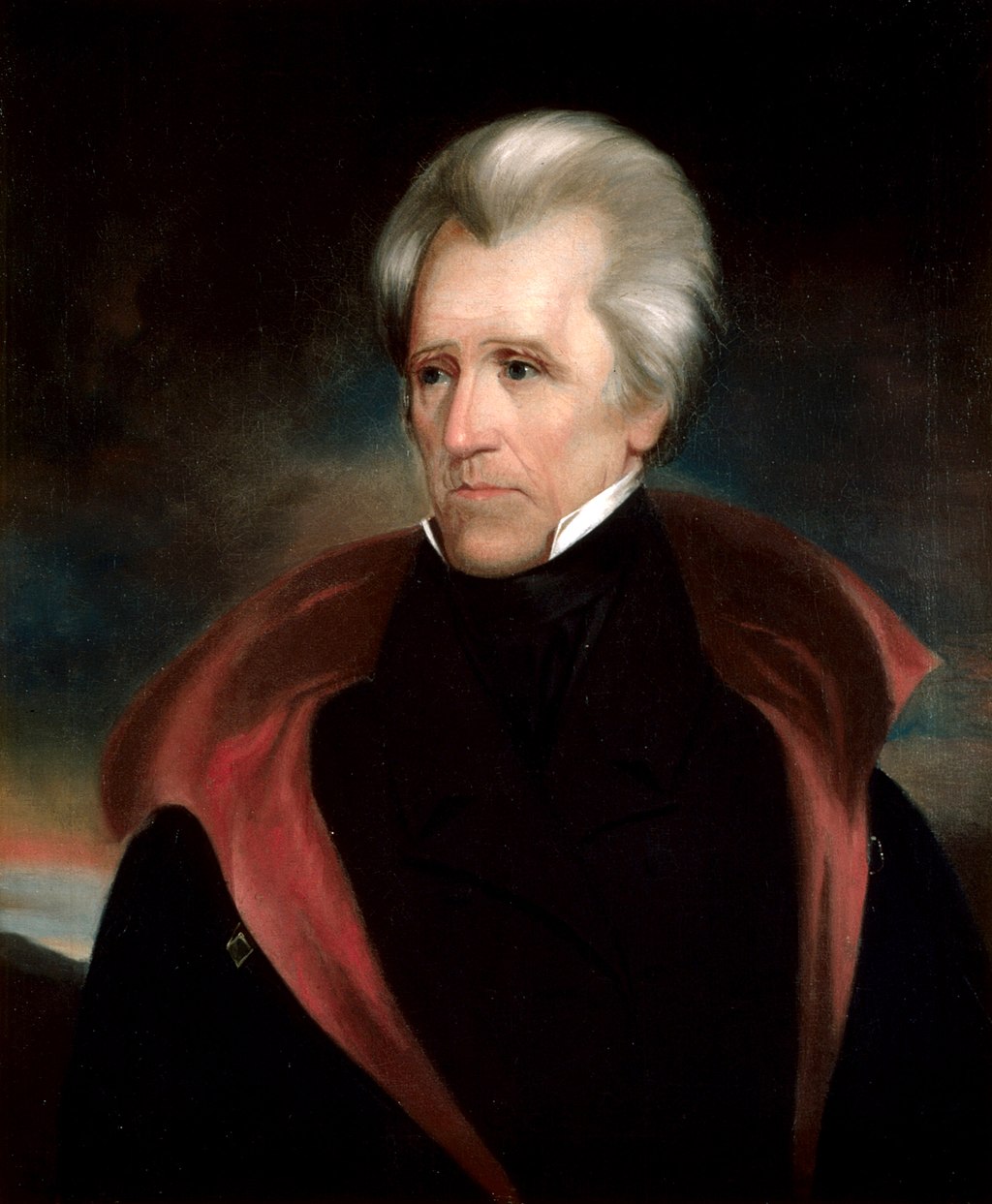

The Electoral College has been controversial long before Donald Trump won the 2016 presidency with a minority of the popular vote, and even longer before he fulminated against his 2020 Electoral College loss. In a historical irony, though, the most vocal 19th Century opponent of the Electoral College was another brash, outsider populist, one who President Trump has spoken of as an inspiration: Andrew Jackson.

The Electoral College has been controversial long before Donald Trump won the 2016 presidency with a minority of the popular vote, and even longer before he fulminated against his 2020 Electoral College loss. In a historical irony, though, the most vocal 19th Century opponent of the Electoral College was another brash, outsider populist, one who President Trump has spoken of as an inspiration: Andrew Jackson.

Jackson famously lost the presidency in 1824 despite receiving the most popular votes and the most electoral votes; after a multi-candidate field denied a majority to any candidate, the House of Representatives chose the runner-up in both counts, John Quincy Adams, as president over Jackson. Jackson instantly alleged his loss was due to a “corrupt bargain” between Adams and House Speaker Henry Clay, who delivered House votes for Adams and was then named Adams’ Secretary of State.

Four years later, Jackson was elected president on his second try — and near the top of his agenda was changing the electoral system that had denied him the presidency in 1824. Jackson wanted to eliminate both the role Congress plays in deciding unsettled elections, and the Electoral College itself.

“To the people belongs the right of electing their Chief Magistrate,” Jackson wrote in his first State of the Union message in 1829. “It was never designed that their choice should in any case be defeated, either by the intervention of electoral colleges or by the agency confided, under certain contingencies, to the House of Representatives.”

Jackson called election reform “one of the most urgent of my duties,” and justified changing the then-generation-old Constitution to fix it: “Our system of government was by its framers deemed an experiment, and they therefore consistently provided a mode of remedying its defects.”

He said the current electoral system was vulnerable to corruption. Jackson took particular aim at the role of Congress in choosing a president, with his own experience transparently near the top of his mind:

in that event the election must devolve on the House of Representatives… it is obvious the will of the people may not be always ascertained, or, if ascertained, may not be regarded.

Politically powerful members of Congress, Jackson wrote, might be able to deliver their states’ presidential vote in Congress to a candidate of their choice: “May he not be tempted to name his reward?” Even without corruption, Jackson continued, “the will of the people is still constantly liable to be misrepresented. One may err from ignorance of the wishes of his constituents; another from a conviction that it is his duty to be governed by his own judgment of the fitness of the candidates…”

And even if all were “inflexibly honest,” the current system meant a president could be elected who hadn’t received a majority of votes — and here one can perhaps imagine him muttering “Adams” under his breath — and “a President elected by a minority can not enjoy the confidence necessary to the successful discharge of his duties.”

With all this in mind, Jackson proposed a constitutional amendment “that the office of Chief Magistrate may not be conferred upon any citizen but in pursuance of a fair expression of the will of the majority,” and to “remove all intermediate agency in the election of the President and Vice-President.” By “intermediate agency,” Jackson meant the system where voters don’t actually elect the president, but rather choose electors who choose the president, and by which the House picks a president if no one wins an Electoral College majority.

But Jackson wasn’t proposing a national popular vote, where whoever got the most votes nationwide became president. (For one thing, not every state actually held a popular vote for president in 1828; South Carolina would hold out against having a popular vote until 1868.) He suggested the amendment might still preserve the Electoral College’s system whereby states’ votes are weighted, with smaller states getting a boost: “The mode may be so regulated as to preserve to each State its present relative weight in the election.”

Despite Jackson’s call for such an amendment, however, Congress did not pass such an amendment. In his State of the Union message a year later, Jackson wrote,

I can not omit to press again upon your attention that part of the Constitution which regulates the election of President and Vice-President. The necessity for its amendment is made so clear to my mind by observation of its evils and by the many able discussions which they have elicited on the floor of Congress and elsewhere that I should be wanting to my duty were I to withhold another expression of my deep solicitude on the subject.

Jackson would repeat similar entreaties year after year, and receive similar inaction each time.

And so the Electoral College persisted unchanged for decades, until revived in 1868 by Jackson’s protegé (and another president with whom Donald Trump is tied), Andrew Johnson.

And so the Electoral College persisted unchanged for decades, until revived in 1868 by Jackson’s protegé (and another president with whom Donald Trump is tied), Andrew Johnson.

Fresh off his narrow acquittal in his impeachment trial, Jackson wrote to Congress of a concern that wouldn’t be out of place in the debates of early January, 2021: “The danger of a defeat of the people’s choice in an election by the House of Representatives remains unprovided for in the Constitution, and would be greatly increased if the House of Representatives should assume the power arbitrarily to reject the votes of a State which might not be cast in conformity with the wishes of the majority in that body” (emphasis added).

Johnson attached to his message the specific language of a constitutional amendment to abolish the Electoral College. He was very much following Jackson’s lines — maintaining the weighting of each state by its total number of senators and representatives, but simply abolishing the intermediary steps of the Electoral College and the House of Representatives. Instead of Congress settling an election where no candidate got a majority, Johnson proposed a runoff election.

Under Johnson’s proposal, each state legislature would be required to draw a number of electoral districts equal to its combined number of senators and representatives, “composed of contiguous territory” and containing “as nearly as may be, an equal number of persons entitled to be represented under the Constitution.”

On the first Thursday in August of election years — note the change from November elections, which were already the U.S. norm in the mid-19th Century — voters would turn out and elect a president and a vice-president, “the person receiving the greatest number of votes for President… shall be holden to have received one vote.” These electoral votes, rather than proceeding through an Electoral College, were to be “immediately certified by the governor of the State” to Congress, which would meet on the second Monday in October to open and formally count the votes. Whoever won a majority of districts was President, but if no one won a majority, “then a second election shall be held on the first Thursday in the month of December… between the persons having the two highest numbers for the office of President.”

As a tiebreaker, if two candidates in the runoff received the same number of electoral votes, the candidate who won the most states became president.

Vice presidents would be elected with a similar system, with the exception that if a runoff was necessary to choose a vice president but not a president, the Senate would instead “choose a Vice-President from the persons having the two highest numbers in the first election,” to avoid the necessity of an entire national election to choose a job that John Adams had famously dismissed as “the most insignificant Office that ever the Invention of Man contrived or his imagination conceived.”

In addition to changing the manner in which U.S. presidents were elected, Johnson also proposed changing the term of the president from four years to six, and limiting presidents and vice-presidents to one term in office.

Given that Johnson had recently been impeached and narrowly acquitted, and had just weeks prior been handily defeated in his bid to be the Democratic Party’s 1868 presidential nominee, he was a lame duck without influence, and his amendment unsurprisingly got even less of a hearing than Jackson had.

In fact, Johnson proposed three other consequential amendments at the same time. In addition to direct election of the president, Johnson proposed the popular election of senators — what later became the 17th Amendment. He called for removing the Speaker of the House and President Pro Tempore of the Senate from the line of presidential succession, something that had been extremely relevant for Johnson, who had no vice president himself, and who if impeached thus stood to be succeeded by the President Pro Tempore of the Senate — who therefore could make himself president by voting to remove Johnson from office. Finally, Johnson proposed changing judicial appointments, including those of the Supreme Court, from life to 12 years.

A foreign visitor to the United States, the keen-eyed future French prime minister Georges Clemenceau, wrote derisively about “the four still-born amendments of Mr. Johnson,” and said that “their greatest fault is perhaps that they reflect too clearly the personal experience of their author.”

But despite being dismissed at the time, one of Johnson’s four amendments would later (in a different form) be adopted as the 17th amendment, and the other three issues — judicial term limits, presidential succession1, and the Electoral College — remain controversial to this day.

None of this, I will note in closing, should be construed as an argument for or against the Electoral College, or for or against the 19th Century proposals discussed here. It’s just interesting when a debate that seems very modern turns out to have very old antecedents.

Sources

- Andrew Jackson, “First Annual Message” (Dec. 8, 1829)

- Andrew Jackson, “Second Annual Message” (Dec. 6, 1830)

- Andrew Johnson, “Message Proposing Constitutional Amendments” (July 18, 1868)

- Georges Clemenceau, American reconstruction, 1865-1870: And the impeachment of President Johnson (Longmans, Green & Company, 1928)

-

For more on the lingering controversy around the inclusion of legislative officers in the presidential line of succession, see Brian Kalt, Constitutional Cliffhangers: A Legal Guide for Presidents and Their Enemies (New Haven & London: Yale University Press, 2012) ↩