Meet Megakota

It started as a joke: an online petition asking President Donald Trump to merge the rural, sparsely populated states of North and South Dakota into a single state, dubbed “Megakota.”

“i think itd be pretty cool to have a state called MegaKota so yeah,” a North Dakota user of change.org named Dillan Stewart wrote.

It’s self-evidently silly — not to mention disrespectful to the state’s namesake, the very real Dakota people. But as the person who once wrote 3,000 words analyzing how barely more serious 2012 proposals to have South Dakota secede from the Union might play out, I’m all for taking silly things to unreasonably seriously. (For the record, such a merged stated would be more respectfully named “Dakota.”)

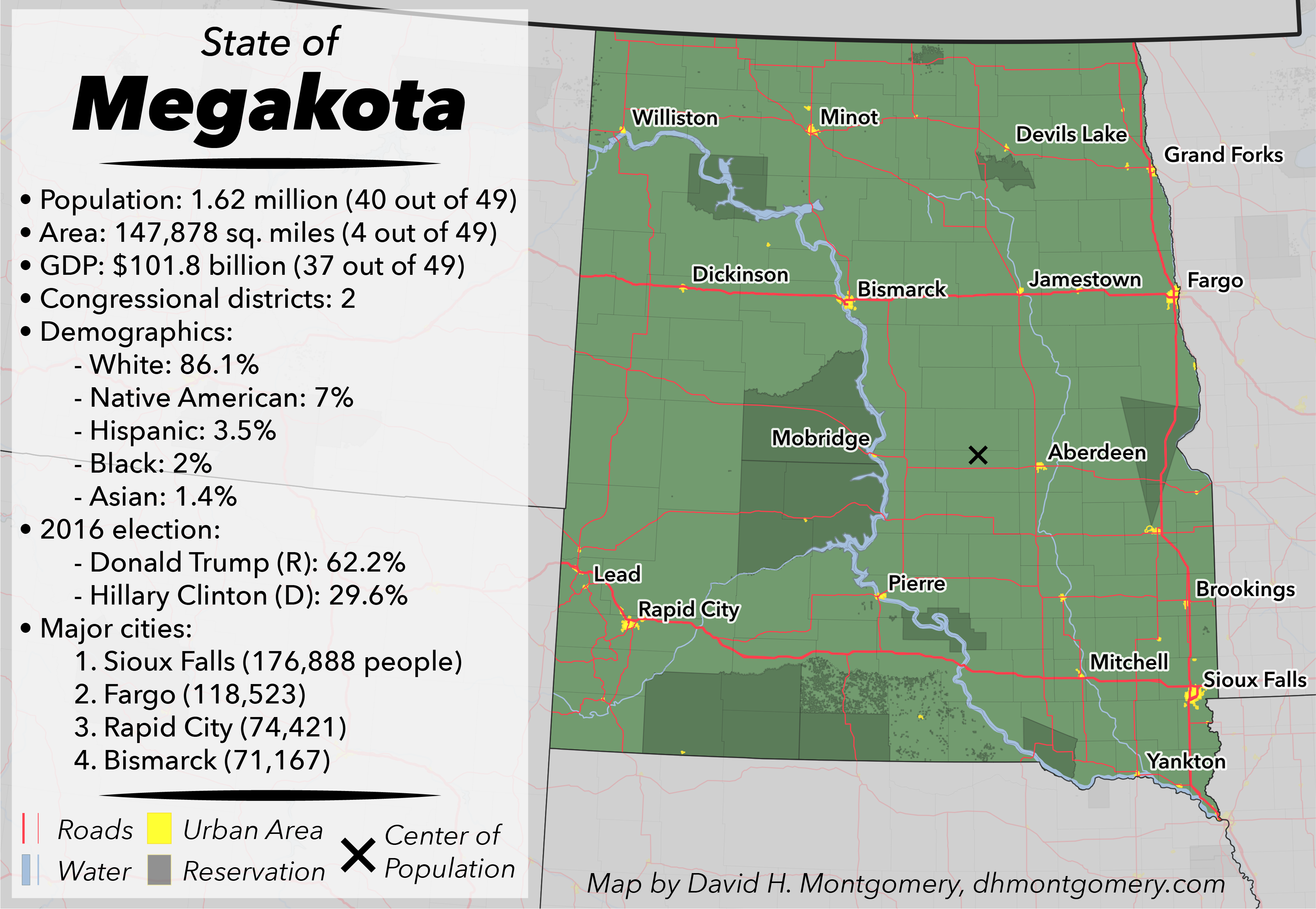

So here’s what the new state would look like. It would be America’s new 4th-largest state by land area, slipping in just ahead of Montana with 147,878 total square miles of area, the 40th-largest state by population with about 1.62 million people, and the 37th-largest by economy with a gross domestic product of around $101.8 billion.

The new state would combine the tourism and financial services industries of South Dakota with the oil and gas revenues of North Dakota, along with both states’ burgeoning agricultural sectors — with around $16 billion in combined 2017 agricultural revenue, Megakota would be the nation’s sixth-biggest farm economy, just behind Minnesota.

Politically, going from two states to one would cost the Dakotas two of their current four U.S. senators. Megakota would have a similar population to Idaho or West Virginia, instead of Alaska and Delaware. But it wouldn’t lose any members of the House of Representatives — with about 1.6 million people it would be comfortably in the middle of the bloc of states with two representatives. On the national level, Megakota would likely be as reliably Republican as North and South Dakota are; Donald Trump received more than 62 percent of the vote from the two states in 2016, and both also now have all-Republican delegations to Congress.

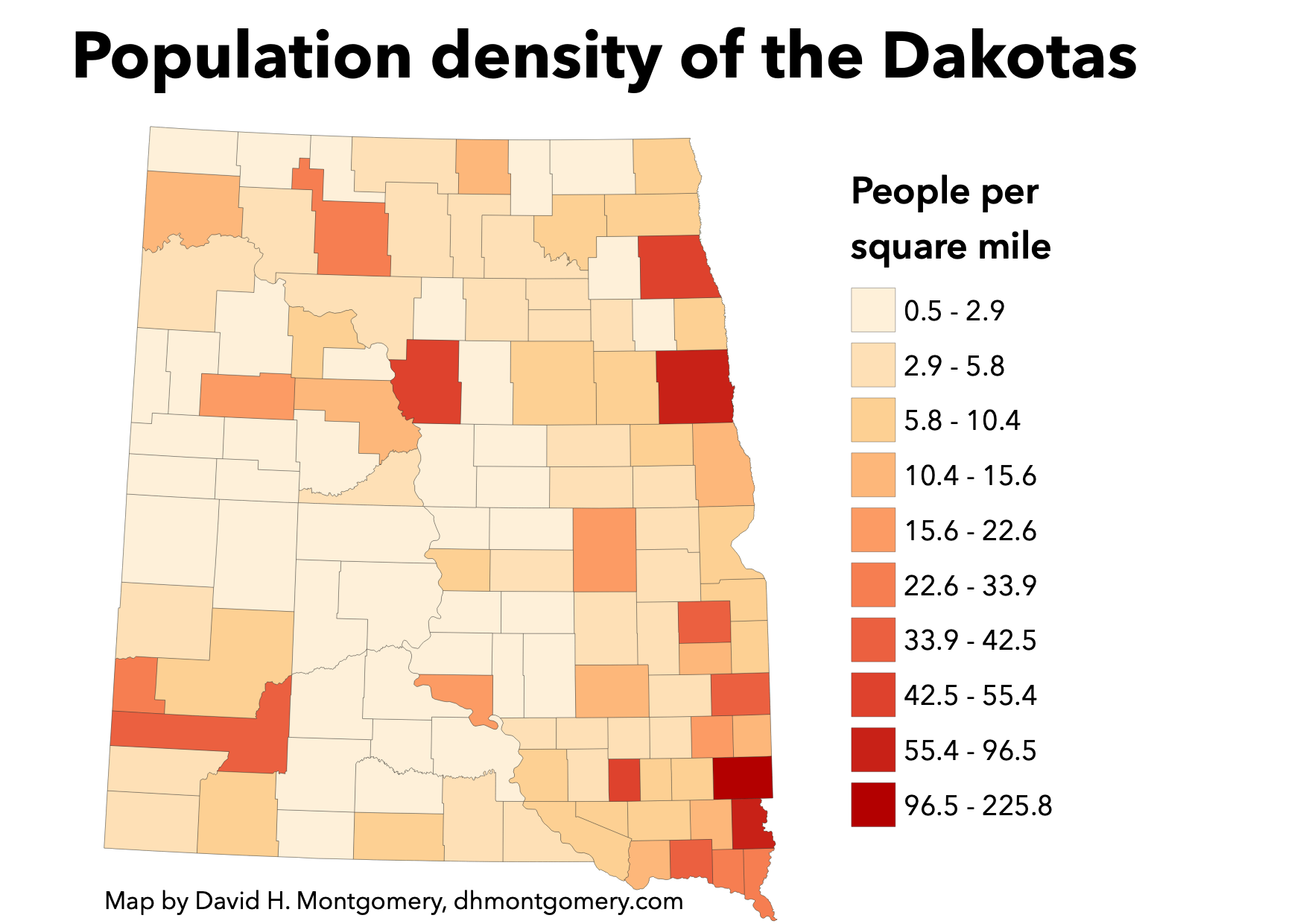

Demographically, Megakota would be among the least dense in the country, as are both of its current constituent parts — Megakota would have around 11 people per square mile, ahead of only Montana, Wyoming and Alaska. What people it does have would be heavily concentrated in the new state’s eastern half, where its two largest cities (Sioux Falls and Fargo) would be located. But Megakota would still have some population centers outside the Interstate 29 corridor, including Rapid City in its southwest and Bismarck in the north-center. Its northwestern oil and gas fields would also provide a big economic engine.

One big decision the new state would have to make is where to situate its capital. Currently both picked central cities as their seats of government, with South Dakota’s in tiny, 14,000-person Pierre and North Dakota’s in 71,000-person Bismarck. But with Megakota’s population so heavily situated in its eastern stretch, the new combined state legislature would have to consider the best location for a new capital. Bismarck is six hours’ drive from Sioux Falls, while Pierre is more than five hours from Fargo.

The center of population for the new state would be in what is today north-central South Dakota, near tiny Ipswich, S.D. Much to the disappointment of the Ipswitch Chamber of Commerce, that thousand-person former railroad town probably wouldn’t get the new state’s dome. Nearby Aberdeen, S.D. (28,388), is the closest large town to the new state’s population center, while Mobridge, S.D. (3,520) could be another option if western interests refused to accept an eastern capital. Either way, the new state’s capital would be fairly remote, and the new state might push to improve the existing north-south U.S. Highways 83 (running east of the Missouri River between Pierre and Bismarck) or 281 (running up the James River Valley through both Dakotas).

It’s highly unlikely that any U.S. state would ever agree to give up its political influence by voluntarily merging with another state, at least not so long as the U.S. political system apportions representation by state as well as population. But if it were to happen, these twin low-population prairie states would be as good a nomination as any. (Their separate creation itself owes much to politics, as national 1880s Republicans sought to bolster their performance in the Senate by creating creating new Republican-dominated states.) In return for some sacrificed political power and a whole lot more driving, Megakotans would gain a larger, more diverse economy and a larger (but no more diverse) population — still small and rural, but through sheer scale, a much more significant player on the national stage.